Trentino Alto Adige. Una regione sostenibile a cura di Pino Scaglione, Chiara Rizzi, Stefania Staniscia con Edoardo Zanchini

torna su“LE ALBERE” IN TRENTO, A NEW ECO-NEIGHBOURHOOD BY RENZO PIANO by Vincenzo Cribari. Photography by Fabio Cella

The new neighbourhood of Le Albere in Trento designed by Renzo Piano is an important operation of urban transformation and reconversion. The way it is defined and the possibility it offers to investigate and test future scenarios, placing itself among the potential cases to which we will refer, both in terms of experiences conducted and also expected results, makes it interesting.

Trentino is important and central in the dynamic of the Alpine space in the centre of Europe. It is located along one of the historic communication axes of the Alps, the Brenner route. This is the principle exchange corridor, as regards traffic numbers, but above all as regards volume of merchandise. The Alps are one of the macro-areas which has long functioned as a large hinge among Europe’s several peoples, cultures, economies and societies, often also with traits that bring them together, but it has also been the scene of great conflicts and wars. In recent years it has achieved recognition in the Alpine Convention and as a common European space. The Alps are the heart of the most important environmental and natural system in Europe, one need only remember the water cycle and the river basins that develop in and leave from this region. It is within their relationships with these places, that the several communities of the Alpine space are trying to construct a new image for Alpine society and for the structuring of what this area offers (1). So, it is within this dynamic and respecting this context that one must place the urban transformations of Trento and with this the new neighbourhood Le Albere.

This new neighbourhood rose on one of the most important and central areas of the city, the object over recent years of lively political and cultural debate. In brief, it has been one of the main themes that have contributed to the choices regarding the recent transformation of the city. The ex-Michelin area, in line with analogous Italian and European experiences where the issue was the fate of large decommissioned industrial areas inside the city, the factory was abandoned and now over the years, it has undergone a process of reconversion and transformation.

It is well to remember that for a small reality like that of Trentino, this intervention took on an important dimension both in terms of investment and resources made available, from both investors and the public administration.

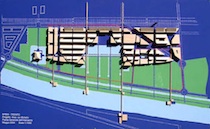

The area covered by the project is slightly over 10 hectares. It is located in an area very close to the historic centre and consolidated city, between the railway and the river. There are difficulties from the point of view of accessibility deriving in large part from the city’s tendency to develop longitudinally along the axis of the Adige and it is wedged among the Alps and crossed by large natural phenomena and man-made infrastructure that run along the valley. Inside this neighbourhood, aside from residential and commercial areas and a large new park covering almost 5 hectares (Trento had 3 earlier parks, but this is now the largest), there will be a new Museum of Science, the Muse, conceived as a centre to spread scientific and didactic knowledge and a new auditorium.

The process that led to formation of the new neighbourhood

The buildings of Le Albere which are approaching completion represent the end of a long and articulated process which since 1998 has involved both institutional and private players.

Michelin started occupying the terrain on which the neighbourhood currently rests in 1924, building a factory which initially worked in the textile sector (rayon for tyres made from cellulose). From 1958 the factory produced steel bands for radial tyres. The plant reached its highest production levels in the 1970s.

In 1998 the factory closed and almost immediately negotiations between the owner and local authorities regarding the transformation of the area started. Initially Michelin offered the 116,000 m² along the river to the city of Trento in pre-emption for about 25 million euro. The city refused the offer and at the same time zoned the area as a mixed area (residential, private and public commercial and services). At this point the pre-emption was ceded to Iniziative Urbane S.p.A, a company set up for the occasion as a public-private partnership representing the credit and entrepreneurial system of Trentino (among others are: Cassa de Risparmio di Trento e Rovereto, SIT (today Trentino Servizi), Dolomiti Energia, L’Instituto di Sviluppo Atesino). Still in this period, in 1999, the Province of Trentino set up a PRUSST (Programme for the urban requalification and sustainable development of the territory) which included the ex-Michelin area and the next year it was approved by the Ministry of Public Works. The operation also represents one of the principal actions in the “Strategic Plan for the city of Trento 2001-2010”.

In 2002, after a first attempt by the city to hold a competition open only to those designers enrolled in the Association of Professional Architects of the Province of Trento, the project was entrusted to by Iniziative Urbane directly to Renzo Piano. One should keep in mind that Trento’s Municipal Council had asked the company to entrust the design to an architect of “international, or at least national, fame”.

There was a certain amount of urban ferment in Trento in this period. Between 2004 and 2005 two variants of Vittorini’s PRG (general zoning plan) were put forward by university professors (Renato Bocchi, Alberto Mioni and Bruno Zanon). Joan Busquets has been one of the main protagonists in the debate on the transformation of the city. Having recently finished experiences in Catalonia and the Netherlands, he proposed a very innovative plan; first of all he proposed burying the rail line that for many years and still today in many circumstances and occasions is one of the urban options open to the city and the entire Trentino.

In March 2004 the Municipal Council of Trento approved the “Guide” Plan made by Renzo Piano; a number of interventions were planned, some of which are the responsibility of the public administration or will be handled by an agreement among the parties, which are fundamental in the overall design of urban requalification and so that the neighbourhood will function. A year later the council approved a plan for subdividing the ex-Michelin area which belonged to Iniziative Urbane. The plan determines that of the 116,000 m² along the Adige, where the factory stood, 70,000 m² will be for public use once the convention between the Municipality and Iniziative Urbane has been signed; a green area to include a park, roads, public squares and waterways (60% of the overall area). The area will have advanced tertiary activities, residences, hospitality and commercial activities (occupying a total of 320,000 m³). There are plans to build a park covering almost 5 hectares with an internal canal system, a science centre and underground parking for 1,800 cars. A stretch of Via Sanserverino, the main road along the bank of the Adige (between Palazzo delle Albere and Via Monte Albere) will be lowered and covered over and a pedestrian-cyclist bridge will be built in the area near Palazzo delle Albere.

Following the master plan of 2004 the design for the neighbourhood has undergone several changes before arriving at its definitive configuration. In the meantime the company Iniziative Urbane has given direct management of the real estate works to Fondo Clesio (a closed real estate fund which is reserved to institutional investors), managed by Castello SGR, whose job it is to take care of all building phases of the operation. The building began in 2008 and was completed in 2012.

In July 2010, the Province, through the Provincial Agency for environmental protection approved the risk analysis document prepared by Castello SGR. In fact a land reclamation procedure had been initiated in the area because pollution had been found in the ground water. However the analyses confirmed that the levels of tetrachloroethylene found were not over the permitted contamination threshold (either for built up land or open land), and consequently the land reclamation project was terminated.

The new neighbourhood and the uncertainty scenarios of the market

At writing the project was nearing completion, the Muse has recently been handed over to the Province. Renzo Piano announced that he “managed to put up this building on schedule and within the budget, almost a miracle”.

In the residential part, the about 320 apartments are built to the most advanced architectonic and energy efficient standards. The buildings have received both a gold level certification according to LEED protocols and certification from Casaclima. The entire complex is served by a single tri-generation power plant which manages the energy system: large areas are covered with solar panels and a heat exchange probe exploiting geothermal energy.

The urban impact is still to be fully defined as there remains a series of works that the municipality has yet to complete, they will move this entire part of the city toward a new system of pedestrian and vehicular flows. It will be above all the solution of the relationship with the historic city and the solution of the crossing(s) of the rail tracks that define the condition of the relationship of the neighbourhood with the rest of the mobility system: pedestrian, cycling and public transport. It is also essential that the neighbourhood not become a cul-de-sac, avoiding that the so-called Polo Sud (the auditorium) amplifies the effect of ‘a closed sack’, with only limited communication with the rest of the city. In synthesis, from the point of view of public and urban space, one of the critical things will be precisely the relationship between the neighbourhood’s internal space and the space of the city, in other words between the delicate equilibrium of relationships, often lost in the manifestations of recent cities, but are easily recognisable and optimally structured in Italy’s historic cities. Managing the way the public spaces of the neighbourhood are imaged will be fundamental for this, above all for that which concerns the system of flows foreseen in the main thoroughfare which connects the two public poles (i.e. the museum and the auditorium). But in this Piano should be a guarantee, as the historic centre of Trento seems to have been changed as a reference to structure its relations with the new neighbourhood.

So we shall have to see how these spaces are lived. The expectations and declarations of the actors, above all the economic ones involved in the process are high, but this is only to be expected as the investments were important and consequently there is a large publicity and communication campaign behind the operation. Though there was a part of the public opinion that was critical, most people think that in the end the apartments will be sold and that the neighbourhood will become one of the most interesting areas in the city, close to the centre and with optimal accessibility to the municipal and provincial service networks.

As is well known however, the current situation, above all as regards the real estate sector, is a very difficult one. There are in effect several critical issues, both those of a local character, on account of the structural situation of the construction market in Trentino, and those deriving from a wider perspective triggered by the crisis of 2008-2009, effects of which are still being felt and have created a very uncertain general framework of future expectations.

As regards the former, one should remember that the Autonomous Province of Trento, together with a series of realities that depends on the entrepreneurial system of Trentino, has for some time sought to organise important innovations in the building sector, using a series of promotional activities connected to the cycles and dynamics of sustainability. I refer to experiences such as the Distretto Habitech, linked to building certification, to Manifattura Domani, an incubator for companies in the field of innovation in the construction sector and the green economy and to experiences like Arca that deal with products in the Trentino’s woodworking sector (among the actors that recently contributed to the realisation of the auditorium donated by the Autonomous Province of Trento to the city of Aquila, also designed by Renzo Piano).

There are at least two questions that concern wider dynamics and should induce reflection.

The first is the possibility that experiences of this type become a model, or that they lend themselves as a base for experimentation and processes that can in some way help to structure ideas at the base of the dynamics that must, first of all, encourage the re-invention of the settled spaces in Italy. We all know how Italian cities have grown (in dimensional terms) since World War II and the low levels the quality of their built up areas have reached, and above all the dynamics that have taken place over the last 20 years, representing the absolute summit of the worst of Italian practices. Rather it is useful to refer to two recent reports (2) that propose elements which are certain to interest the transformation and requalification of Italian cities and in particular the role that so-called eco-neighbourhoods could assume in the future.

The second consideration involves some thoughts on the (social and economic) dynamics and processes used during urban reconversion and transformation projects, as they involve a series of synergetic coactions that structure the relative systems of choices and values. Let us look at a case which is easy to represent: whether to build in compact groups or spread out, the former requires more organisation of the processes that govern the systems of the transformation action; thus on the one hand making it necessary to put together an offer of methods and equipment which are first of all effective, but on the other hand it is necessary to explain to the average citizen why it is preferable to cede a part of his/her freedom and independence to private organisations – as for example the large financial holding companies that manage real estate funds – to build those parts of the city that herald a better quality of life. Within this dynamic, between the two extremes, one should seek new interpretive tools, useful in re-inventing and activating the change, innovation and transformation of current conditions.

(1) See also W. Batzing, “Le Alpi. Una regione unica al centro dell’Europa”, Bollati Boringhieri

(2) I am referring to ‘Ambiente Italia 2011, Il consumo di suolo in Italia’, edited by Duccio Bianchi and Edoardo Zanchini, and the document ‘Ecoquartieri in Italia: un patto per la generazione urbana’ edited by AUDIS, GBC Italia and Legambiente.