The Archipelago of Knowledge 1

From Research to Project

Paolo De Martino, Francesco Garofalo, Carola Hein

Introduction

The relationship between a city and its port, is undoubtedly one of the most conflictual both because of its complexity and because of the diversity of laws, rules and actors involved in the cultures and planning logics of both, the city and the port. They are the result of different historic traditions and practices as well as different geographic and political contexts. These factors, which over the centuries have given shape to an urban puzzle2 and to a spatial and social separation, have become key elements in attempting to understand the delicate city-port relations.

The concept of archipelago3, as used here is a planning and methodological instrument, that includes, on the one hand the idea of the difficulty of coexistence, the difficulty of keeping things together in their diversity and on the other hand the will to work on existing spaces, practices and logics to modify them and build, like in an archipelago, new geographies and systems of spatial relations. So working between the city and the port forces architects, city planners and legislators to rethink both their planning logics, which consider the city and port as two separate elements, and areas of competence, identifying the intersecting elements of the different scales, within which to imagine scenarios of change and possible hybrids.

The case of Rotterdam can stand as an emblematic example. Rotterdam could be read as a large port attached to a city if one considers that some of the new expansion of the former is about 40 kilometres from the urban centre. So the city and the port are separated from both physical and spatial points of view. However, this separation has been compensated for over the years by close collaboration among the local and national institutions, private subjects and research institutions to define a shared planning agenda that looks on the port as a strategic element of the city’s infrastructure, but at the same time one that can recreate a contact in the collective memory of its inhabitants.

Con-fines and frontiers between the city and the port

Ports though spatially defined, are perceived by the community as urban subtractions, frontier regions, as on the confines between the sea and the city, spaces dedicated to relations with freight more than to relations among individuals, “non-places of the supermodern”4 a product of globalisation, spaces that are segregated and regulated by their own laws, different from those that regulate the cities (fig. 1).

An etymological analysis of the two terms shows the clear difference between confines, as a geographic line of separation – but also of union – and frontier with a different cultural interpretation. The two terms, both from Latin are only apparently synonyms. On the contrary they hide profound differences. The frontier was the limit between the known and the unknown; the confines was the line that traced the limit of one owner, territory or country. Confines means the division between two areas, but it is a line which the two sides have in common and share; con-fines suggests that that conclusion is in common, and so not only a line of separation, but also of union and sharing. The complexity of the dynamics of harbours today, taking into consideration the tangible and intangible relations that have dissolved geographic limits, makes it advisable that we move our attention to an analysis of their confines and away from their elements of division.

In the demarcation between city and port the frontier and confines – each meaning division – coexist, making port areas inaccessible but at the same time unknown. Cities and ports are separated by confines of differing nature. In fact administrative, physical and perceivable confines separate a seaside city from its port. The city and the port host different flows changing and transforming in differing temporalities.6 Finally, the city and the port are planned and managed by different institutional subjects with plans and rules that are not always on the same plane and so the dialogue when it occurs between them is forced.

The interface, refers to the different places in which the city physically encounters the port, is the place of conflict5 between different spaces, flows, subjects, interests, visions and temporalities7.

In many cities this conflict has been resolved thanks to planning choices that determined a distancing of infrastructure and the most difficult part of the port machinery away from the city (see the case of Rotterdam). In many other realities, above all in the Mediterranean this has not occurred, both because of a lack of strategic vision and for morphological problems and because there a differing planning culture exists that considered the port as a terminal element of a voyage rather than as a hub for a wider logistic system, often making the port appear as a barrier between the city and the sea (see for example the case of Naples).

So a redefinition of the terms of the relation has become necessary and the project “Archipelago of Knowledge” proposes a different interpretation of the confines between Rotterdam, the city and its port. These confines become places for possible dialogue and negotiation, a line that divides but at the same time holds the different elements of the urban mosaic8 together.

Port of Rotterdam

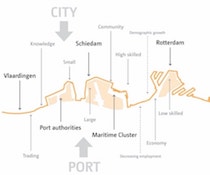

Rotterdam’s harbour landscape, which extends for about 40 kilometres from the city to Hoek van Holland toward the North Sea, has a strong industrial character with deposits and oil refineries that occupy a large part of the port area. It is a fragmentary landscape in which the urban areas interface with the port in differing ways generating a series of different and discontinuous confines (fig. 2, fig. 3).

Up to the second half of the 19th century, thanks also to the types of commerce which were different from those of the present, the national plan considered the port an urban element and an integral part of the landscape. The “Boompjes”, the historic walkways that lined the historic nucleus of the port testify to the port being used as an internal element of the urban and social dynamic. Technological and infrastructural progress transformed ports radically throughout the world just as it rendered their relations with their cities conflictual. In the case of Rotterdam starting in the second half of the 20th century the port authority and local agencies collaborated to improve the relations between the city and the port. This has meant that the port has moved further from the city so that it can become more competitive on a global level (fig. 4).

This phenomenon has moved attention to the margin of the delocalized port infrastructure, a malleable9 and porous10 area which has over time found new uses to help in joining the city with the old port areas (fig. 5).

Over the years Rotterdam has shown itself to be an example of a city changing constantly as if it had different personalities. In front of the city on the northern bank is an open and spatially extended limit where the western neighbourhoods of Rotterdam and the cities of Schiedam and Vlaardingen share a clear separation with the port areas; or on the southern bank with the closed spatially circumscribed lines where the urban centres of Heijplaat, Pernis and Rozenburg are surrounded and segregated by other port areas.

The project “Archipelago of Knowledge” concentrates on the first area, on the 9-kilometre interface that divides the port from the scattered urban territory of Rotterdam, Schiedam and Vlaardingen (fig. 6).

Divisions and distances

The project “Archipelago of Knowledge” represents a new spatial strategy for the city of Rotterdam. It concentrates on reformulating the relation between the city and the port by focusing on the confines as an autonomous research object, analysing the benefits of a boundary that becomes space rather than line, a con-fines, transition area between the two conditions.

Currently the confines are sharp, net, practically impassable and multiple. The demarcation line between the city and the port is defined by “no-go zones”, crossed only by port employees: the proliferation of fences and controlled gates are a symbol of the area’s inaccessibility. Much of this limit is strengthened by infrastructure, creating a further visual, acoustic and spatial barrier; the defense bank (dike), protects the urban part leaving the port part vulnerable, creating a further tridimensional demarcation between the two conditions. The different administrative realities, the separating infrastructure, the distance between those who work for the port and the port itself – almost uninhabited – only adds to the physical division, the perceived distance: the port as a frontier, as unknown, aside from an inaccessible space. As we see from the harbour’s economic projections11 (fig. 7), elaborated by Erasmus University of Rotterdam, the paradoxically increasing difference between the growth in added value and the decrease in employment, can do nothing but increase this facetted division.

The port’s physical inaccessibility can be considered as the public’s being denied accessibility to the water, in fact port areas function as a barrier between the inhabitants and the Maas River. Of the 26 kilometres of waterfront considered only 3 kilometres were accessible, thus only 11% of the linear development along the water is accessible to the public, which lives next to the port but without the benefit of direct contact with the water.

There are many difficulties in tackling these limits and in proposing new solutions: the port’s interests, the impenetrability of the systems that govern it, the number of actors involved and the geographic extension of the boundaries makes an effective solution extremely complex.

But it is precisely the large scale, by most considered a weakness that the project makes its strength. The linear development along the Maas crosses differing territorial and administrative conditions and it joins them in their relationship with the port and in their lack of relationship with the water. The limit is shared and once the benefits of a new spatial relationship have been brought out and what is in their common interests identified these different realities can negotiate these new spatial relations.

And the matrix of the proposal “Archipelago of Knowledge” is exactly this: make this line into a surface (fig. 8).

Archipelago

The goal of the proposal is to increase the public’s accessibility to the Maas from 11% to 100%. This spatial revolution is pursued by the excavation of new canals, that by isolating the active parts of the port create a continuous waterfront between these latter and the urban area. The port areas that are not accessible would become islands and the city would gain uninterrupted access to the water. This new line of waterfront will not only give back to the city its outlet on to the river, today denied by the port, it will become a new vector for public transport and logistic space for the harbour area (fig. 9).

Knowledge

The new waterfront is an accessible public space available to the city and, contemporarily, available to the port. If a port’s research, knowhow and management services are fundamental support services, it is also true that they are often located geographically far from the ports themselves. The new waterfront can host these functions and on the one hand they will benefit from their proximity to the port, on the other they will profit from being concentrated and located in an urban area, gaining in visibility and integration. The research and knowhow that support a technologically advanced and logistically avantgarde port can generate an ‘open campus’, a new urban area, hybrid and shared between the city and the port (fig. 10).

From conflict to negotiation, from line to surface

The city and the port are regulated by different dynamics and planning. The interests of different subjects are responsible for change in each and this change follows different temporalities. Today debate and contemporary city planning projects are going back over the themes of urban regeneration at the edges of large infrastructure projects and reformulating the themes of relations between ports and territory, shifting attention to areas that have been decommissioned or are in the process of being decommissioned and can have a strategic role in re-establishing morphological, cultural and institutional relations between ports and their cities in different scales.

The concept of porosity has become the material of the project and the instrument used in reading the space between the city and the port. Empty or full spaces, decommissioned buildings and abandoned areas interpenetrate favouring the possibility of new phenomena of spatial and social intermixing.

The waterfront proposal is only apparently a line, rather it is based on a new analysis of porosity, defining harbour ‘islands’ and restoring to the public the banks overlooking the river. Further it is integrated with the ‘open campus’ function and includes public service areas like green spaces, sporting facilities and playgrounds. The line becomes an area, a surface.

This is the change in concept at the base of the proposal, the line, the confines becomes a surface of con-fines; not a line of division between two different territories, but an area shared by two realities, that can draw mutual benefits from the overlapping. This con-fines will establish a new relation between the city and the port perpendicular to the river, and longitudinally among the several territorial and administrative realities. A territory of mediation and speculation which will seek to attract various stakeholders, from local communities, interested administrations, port authorities and the entities that make up the maritime cluster, and bring them together with the common objective of mending a physical-temporal-administrative division that has separated the port from the city and bring them into a new system that will work to their mutual advantage.

Notes

1. Il progetto “Archipelago di conoscenza” è stato elaborato nel 2016 da Openfabric, Kartonkraft, Mauro Parravicini Architects, Noha, Movemobilty e commissionato da Deltametropool (Research Coordinator), Uenl (Coordinator), Province South-Holland, Regio Drechtsteden, MRDH, Regio Alblasserwaard-Vijfheerenlanden and Gemeente Rotterdam. Per maggiori informazioni visita il sito http://www.openfabric.eu/projects/archipelago-knowledgerotterdam-netherlands/. Ultimo accesso 23-10-2017.

2. B. Secchi, La Città Dei Ricchi E La Città Dei Poveri (Bari: Laterza, 2013).

3. F. Indovina, Dalla Città Diffusa All’arcipelago Metropolitano (Milano: Franco Angeli, 2009).

4. M. Augè, Nonluoghi. Introduzione a Una Antropologia Della Surmodernità (Paris: Elèuthera, 1992).

5. C. Hein, "Temporalities of the Port, the Waterfront and the Port City," PORTUS: the online magazine of RETE 29 (2015). Hein, C. (2016). "Port cities and urban waterfronts: how localized planning ignores water as a connector." WIREs Water 3: 419–438. doi: 10.1002/wat2.1141

6. R. Pavia, and Di Venosa, M., Waterfront. From Conflict to Integration (Trento: LISt Lab Laboratorio. Internazionale Editoriale, 2012).

7. Hein, ibidem.

8. M. Russo, Città Mosaico Il Progetto Contemporaneo Oltre La Settorialità (Napoli: Clean, 2011).

9. "Harbour Waterfront: Landscapes and Potentialities of a Contended Space," TRIA 13, no. special issue (2014).

10. Il concetto di porosità in riferimento ai fenomeni urbani affonda le sue radici nel pensiero del filosofo tedesco Walter Benjamin che nel 1925 scrisse una raccolta di saggi brevi, intitolata “Immagini di città” contenente una serie di immagini urbane. La metafora è stata è stata usata da Walter Benjamin prima per descrivere la città di Napoli e poi più in generale il vivre ensemble mediterraneo. Il concetto è stato poi ripreso da studiosi e urbanisti contemporanei come Bernardo Secchi (Secchi., Paola Viganò (P. Viganò, Secchi, B., , Antwerp, Territory of a New Modernity (Amsterdam: Sun Publishers, 2009). e Cristina Bianchetti (C Bianchetti, Il Novecento È Davvero Finito (Roma: Donzelli, 2011). Il concetto di porosità viene riattualizzato per rileggere e reinterpretare i fenomeni di dismissione e frammentazione del territorio contemporaneo.

11. The strategic value of the Port of Rotterdam for the international competitiveness of the Netherlands.

URL: https://goo.gl/GmbWGa

Bibliography

Augè M., (1992), Nonluoghi. Introduzione a Una Antropologia Della Surmodernità, Elèuthera, Paris, FR.

Bianchetti C., (2011), Il Novecento È Davvero Finito, Donzelli, Roma, IT.

Hein C., (2015), "Temporalities of the Port, the Waterfront and the Port City" in PORTUS: the online magazine of RETE vol. 29.

Indovina F., (2009), Dalla Città Diffusa All’arcipelago Metropolitano, Franco Angeli, Milano, IT.

Pavia R., Di Venosa M., (2012), Waterfront. From Conflict to Integration, LISt Lab Laboratorio Internazionale Editoriale, Trento., IT.

Russo M., (2011), Città Mosaico Il Progetto Contemporaneo Oltre La Settorialità, Clean, Napoli, IT.

Russo M., (2014), "Harbour Waterfront: Landscapes and Potentialities of a Contended Space" in TRIA, vol.13, special issue.

Secchi B., (2013), La Città Dei Ricchi E La Città Dei Poveri, Laterza, Bari, IT.

Viganò P., Secchi B., (2009), Antwerp, Territory of a New Modernity, Sun Publishers, Amsterdam, NL.