Condo(m)ania, A view from Italy.

Lorenzo Pignatti

Condo(m)ania, A view from Italy.

Lorenzo Pignatti

When I first visited Toronto in 1979 the centre of city was mostly characterized by a cluster of towers in the downtown area with the Royal York Hotel and Union Station in front of them and by a huge empty void, the Railway Lands, situated between the city and Lake Ontario. This void, quite exceptional for a modern North American city, separated the city from its water-body and disconnected the urban fabric form its waterfront. The Railway Lands were crossed by the Gardiner Expressway, an elevated highway that then ran (and still does) parallel to the shore and was considered, by most architects and urban designers of the time, one of the major obstacles for the relationship between the city and Lake Ontario.

Another element of high visibility, but not a real icon, was the CN tower, at the time the world’s tallest structure, an isolated object that had neither any relation with its context nor any appealing esthetical value. It looked like a big syringe.

However the image that could be then appreciated while driving along the Gardiner towards the city centre was superb. For a young Roman architect who was then used to appreciating different urban landscapes, this view, mostly seen on a winter clear afternoon, was a condensation of the real character of the North American city, the sense of its scale and the role of vehicular infrastructure within the modern city.

The above mentioned cluster of towers was a combination of six/seven towers, set alone in this beautiful image. The most interesting piece of this “volumetric composition” was the group of three towers designed and built by Mies van der Rohe as the Toronto Dominion Centre in 1967. The TDC was created following the forward-looking vision of Phyllis Lambert, a person who has contributed immensely to the urban and architectural debate in Canada. The three towers are similar to most of Mies’ other North American buildings, starting from his most famous Seagram Building along Park Avenue in NYC, but the overall composition of the various elements at TDC is unique and has no equal among his other projects. If the Seagram Building is purely an object with a public space in front of it, in the Toronto project the different elements of the complex create hierarchy, relationships with the surrounding context and, in fact, a strong urban framework. The positioning of the towers together with the low banking pavilion creates a single open public space with its perimeter traced by a clearly defined raised podium as a gesture to further idealize the project itself. Moreover, the quality of the materials and detailing, the relationship of the buildings within the block, the dynamic quality of the outdoor public space and, finally, the underground concourse, were all a great lesson on modern urbanism and architecture. The TDC is so perfect, rational and controlled that it certainly stands as an icon in the city of Toronto. When some years later I was able to visit some of the interior corporate spaces, I could confirm in person the quality and perfection of this complex.

Going back to the view of the downtown area from the Gardiner, next to the TDC there were other tall towers, all headquarters of different financial institutions. The Bank of Montreal was a simple and quite banal white tower taller than the others, the Bank of Nova Scotia was a slightly more articulated tower sheathed in intense red granite and, finally, the silver and simple volume of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, designed by I.M. Pei.

So there was a cluster of four bank towers of four different colours that revealed the role of Toronto as a primary financial centre, as well as the iconic role that commercial banks had in North America. Thus the icons of the city were not monuments or cathedrals but rather the corporate and bank headquarters, declaring how important business and finance were in contemporary life.

The image that Toronto was offering was simple and clear and it certainly attracted the attention of a twenty-five-year-old Italian architect who was visiting North America and with a particular interest in Canada. As a result, the following year I enrolled in the Urban Design Master’s Program at the University of Toronto, School Architecture, an event that initiated my long and beautiful academic career at the University of Waterloo, teaching and working between Italy and Canada.

The image of the four bank towers was complemented by the surrounding landscape that also included the Railway Lands and Lake Ontario. As I said earlier, this was the view enjoyed by those travelling along the Gardiner Expressway. Built in the mid-1950s, it is an east-west urban artery that runs across the Railway Lands which lie between the central core of the city and Lake Ontario. The Gardiner was another iconic element of the city, a true monument to modernism and to the North-American dream of the automobile. The Gardiner allowed a fast approach to the downtown area, it was elevated from the ground leaving the soil unoccupied for industrial uses and was a concentration of urban infrastructure with a sequence of continuous concrete pilasters, ramps and secondary lanes built on a piece of land that was becoming more and more vacant and un-used.

Of course the Gardiner was also seen as an urban barrier that was further separating the city from its lake, but, from a different perspective, the Gardiner was the symbol of a new era, a positive belief that was the moving force towards a period of wealth and prosperity. The Gardiner allowed people to drive at a raised height and enjoy the view of the lake on one side and the core of the city on the other. It was a futuristic experience, were velocity was instrumental in enjoying this great urban vision.

Thus the image of Toronto was compressed in four elements, different but complimentary to each other; the towers of the Central Commercial District, the Railway Lands, Lake Ontario and the Gardiner Expressway. Another building that represents Toronto’s modernity is the Toronto City Hall designed by Viljo Revell and completed in 1965. The two semi-circular towers that form a sort of hug, the central council chamber, the pool of water and the arches spanning above it, form a unique combination of architectural and urban significance, representing the great multi-cultural and multi-ethnical character that the city, and Canada itself had started to embrace in those years. So the mid-60s were instrumental in giving Toronto an image of real modernity and an identity that combined both the image of contemporary capitalism and a unique opening to new people, new cultures and to diversity in general.

Is this image still valid?

Certainly not

The present has given to Toronto an entirely different image, characterized by land exploitation and aggressive urban development. The Railway Lands that for decades remained empty awaiting a strong urban vision for their future have become the site of one of the most massive episodes of urban growth that Toronto has ever had, with the construction of hundreds of new towers, new condominiums, or better, condos.

There is a sort of condo-mania that is obsessively using any piece of available soil, showing no desire of thinking about a specific idea of the city, of creating meaningful open public spaces (refer to the precedent of the Toronto Dominion Centre) and creating hierarchy and diversity in the built form except that of amassing volumes over volumes.

The agglomeration of towers in the downtown area is extensive and dense. There are no views towards the Lake and driving along the Gardiner Expressway no longer offers the futuristic vision that was described before since the traffic lanes are completely hemmed in by buildings. While in other parts of the city the urban grid has been able to control and characterize urban development, here the grid is absent and the framework of streets and public spaces has no coherency. The few open public spaces are restricted, windy and uncomfortable. While walking through this section of the city, one feels desolate and seeks only to reach the lake as fast as possible. The proximity among the buildings does not create a sense of a dense city, like, for instance in NYC where buildings are aligned along wide avenues, in Toronto there is a sense of claustrophobia and confusion.

This is not a criticism of urban density that in reality is one of the requirements for a sustainable city, but is a criticism of a city that has created density without a clear urban pattern and through a simplistic repetition of the same urban typology, the condo.

The architecture of these condos is poor, repetitive and without any quality. Every tower is clad in huge panels of glass from floor to ceiling that are supposed to offer amazing views towards the lake, has small and badly designed residential units whose only element of variation seems to be the form of the balconies, spaces that I imagine the inhabitants of the top floors find difficult to use during the cold and windy Toronto winters.

It is clear that the present transformation of this portion of the city has been in the hands of developers and respected architects have, with few exceptions, been excluded from these jobs. It seems that the city has abandoned this section of Toronto and concentrated rather on its waterfront where a series of public spaces and public projects of a certain quality have been developed over recent years.

The web is full of sites like “torontodowntowncondosblog” that describe the unique moment where the market increases and the sales of apartments register an amazing peak. The economy seems to support this moment and the number of condos and other buildings that are under construction in Toronto is just amazing. There are very few places around the world that are enjoying such a moment. But for how long can this continue?

This phenomena is quite similar to what happened in Italy in the Sixties where large urban developments were controlled by “palazzinari”, a derogatory word that indicates developers who built generic apartment buildings, the “palazzina” (somehow similar to the present meaning of the North American condo), without paying any attention to the city or its public spaces and whose only interest was fast profits through land exploitation with cheap and generic architecture.

Viewed from Italy, this phenomenon could be seen as enviable since we are experiencing a complete lack of building activity due to a serious economic crisis, the end of which is still not in sight.

However, as a great friend of Toronto, I just think that all this is happening too quickly and leaving no time to reflect on the implications of such urban growth. I had been absent from Canada for 5 years until I returned to Toronto twice this year. The image that I used to appreciate when driving east along the Gardiner Expressway to reach the centre of Toronto is gone forever in less than half of a decade. I cannot recognize Toronto anymore, it seems a generic city without character, a city like many others, not the one that was driving for modernity in the late 60s and that I later appreciated in the late 70s.

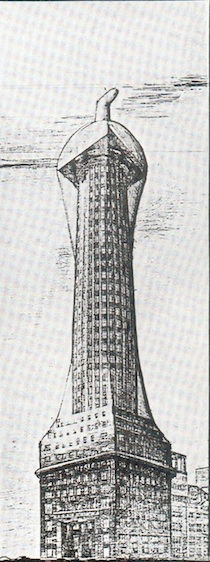

One further image comes to my mind about towers and skyscrapers. In the famous competition for the Chicago Tribune in 1922, Adolf Loos presented one of the most provocative schemes for a tower, a tall Doric column. In 1980, a book entitled “The Tribune Tower Competition” edited by Robert Stern, Stanley Tigerman, both true post-modern architects, included a series of late entries inspired by a critique to modernism. One of these late entries was the same Doric column by Adolf loos, covered with a big condom.

The condom alludes to preservation and immunization. If we are aiming for new, sustainable and coherent urban development, we need to immunize our cities from this condo(m)ania, or this aggressive model of a city completely geared to economic profit, mass architecture and lack of quality.