Planning and density issues in Toronto’s Hyburbia

Planning and density issues in Toronto’s Hyburbia

Christopher Hardwicke and Sean Hertel

hybrid [ˈhaɪbrɪd]

n

1. (Life Sciences & Allied Applications / Biology) an animal or plant resulting from a cross between genetically unlike individuals. Hybrids between different species are usually sterile

2. anything of mixed ancestry

3. (Linguistics) a word, part of which is derived from one language and part from another, such as monolingual, which has a prefix of Greek origin and a root of Latin origin

adj

1. denoting or being a hybrid; of mixed origin

2. (Physics / General Physics) Physics (of an electromagnetic wave) having components of both electric and magnetic field vectors in the direction of propagation

3. (Electronics) Electronics

a. (of a circuit) consisting of transistors and valves

b. (of an integrated circuit) consisting of one or more fully integrated circuits and other components, attached to a ceramic substrate Compare monolithic [3]

[from Latin hibrida offspring of a mixed union (human or animal)]

hybridism n

hybridity n

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged © HarperCollins Publishers 1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003

hyburbia [ˈhaɪˈbɜːbɪə]

n

1. (Urban Planning/ Theory) an urban form or place that is derived from a cross between urban and suburban morphologies and/or building typologies. The Greater Toronto Area is an example of an urban area that is approaching hyburbia.

© Hardwicke, C. & Hertel, S. 2013

Canada’s Toronto region could be considered a “middle child” of suburban form: less sprawling than those in the United States, but more sprawling that those in Europe. In fact, Toronto and its surrounding region of over 6 million people has characteristics from both of these areas. For example: Toronto’s inner and outer suburbs have highway-oriented low density tract housing with two cars in every driveway emblematic of the “American Dream,” as well transit-accessible tower-in-the-park development prevalent at the edges of many European urban centres.

Toronto, therefore, is rather unique in the world in terms of its suburban form; further supporting the notion that, while suburban development is a universal phenomenon, the form it takes is far from uniform.(1) This article will thereby explore the form and formation of hyburban development in Toronto, and explain what is uniquely and not so uniquely “suburban” about it. Beginning with a history of (sub)urban development in Toronto, the article will explain the processes and resulting forms of suburban development throughout over a century of “urbanization”, and then look to the present and future prospects of peripheral development around, and ways of life in, North America’s now fourth largest city.

Unplanned and planned sprawl

Unraveling the popular discourse about the suburbs reveals at its core the twin nuclei of sprawl “sprawl” and “unplanned.” But, at least in the Toronto case, this is not the whole story. While early (early 1900s) suburbanization was largely improvised by individual owner-builders clustering strategically just beyond the reach of streetcar termini and around factories establishing in the low-priced (and generally unserviced) periphery(2), the process of mass government-enabled and market-driven suburbanization as we have come to know it today coincided with the end of the Second World War, as in the United States. Unlike much of the pre-war development, this suburbanization was not only planned, but supported by massive government investments in road, transit and sewer infrastructure that, simultaneously, led and supported market demands.

In fact, modern planning as we know it today in Toronto and the province of Ontario was really borne out of the era of mass suburb-building that coincided with the end of the Second World War. In fact, this period which continued through the 1950s is considered by many to be planning’s “Golden Age.”(3) Rather than subscribing to the thought that the rise of suburban development was the end of planning, it could actually be considered its beginning; in the sense that rampant suburban growth gave rise to formalized regional planning in Toronto, and the forging of lasting linkages with the provision of infrastructure and social services.

This is this first departure point for the Canadian suburban experience, compared to the apparent development free-for-all in the United States. Quite simply, Canada’s sprawl was meticulously planned and actually encouraged by government – instituting a governance structure for the coordination, financing and construction of growth with the required infrastructure. (4)

The creation the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto by the Province of Ontario in 1953 is credited for the emergence of this suburban planning paradigm in the Toronto region and other large urban regions within the province. “Metro”, as it was known, was an “upper-tier” municipal government that coordinated planning, infrastructure and social services across the city proper and its five “inner suburbs”. Metro ceased to exist at the beginning of 1998 when the province ordered the amalgamation of Toronto with its inner suburbs to form what has been coined the “megacity”.

Giving rise to a new kind of suburb

The “poster child” for the old Metro model suburb-building is the community of Don Mills; with its curvilinear streets, mix of bungalows, townhouses and mid-rise apartments, surrounding a shopping mall and other services, Don Mills became the suburban prototype for at least four decades. Metro not only made developments like Don Mills possible, but created an altogether new way of bringing the suburban dream to market. And this dream, under Metro, included high-density living, transit, and social services as well as the requisite detached home with a yard and a car in the driveway. This leads to a second departure point: transit-supportive densities.

Toronto’s planned low-density “sprawl” was punctuated with high-rise apartment buildings, located at highway intersections and along arterial road corridors in within the first waves of post-war suburban expansions, and especially over a 20-year period beginning in the mid to late 1950s. In control of the Toronto Transit Commission, the Metro government ran high-frequency bus services along these high-density corridors; funneling suburban commuters relatively quickly and cheaply (a zone-based fare system was eventually scrapped, having the effect of heavily subsidizing suburban trips) to subway lines leading into the downtown.

Toronto architect Graeme Stewart has studied suburban Toronto’s apartment towers extensively, and says:

“In many respects, portions of Toronto’s suburbs more closely resembled British ‘New Towns’ or Soviet dormitory blocks than the suburban communities typically associated with North America. However, unlike the European experience, the majority of Toronto’s apartments were the result of market forces. They were built by large corporate developers who saw young professionals and their families as a lucrative consumer base.”(5)

The suburb of necessity

While suburbanization and suburbs have often been associated with class ascendancy, including what American planner Robert Fishman has described as “bourgeois utopias”(6), the “suburban dream” in Canada was one borne more out of necessity, rather than desire.

Converse to the typical American story, or tragedy, of “white flight” that often typifies the suburban experience there, Canada’s suburban expansion was generally driven by the need to find a large enough home that families could afford. Rather than a “push”, the Canadian force of suburbia was rather a “pull” from downtowns that were, as they are today, quite livable and desirable but less and less so from the perspective of affordability.

For many, the suburbs are viewed as “holding areas” until they are able – whether it be coming of age, or having the financial means, or both – to settle in the “city” or even downtown. This is not to say, however, that the Toronto suburbs are not desirable places to live – whether it be for a stage of one’s life, or entire lifetime. Don Mills, for example, is arguably one of the more desirable (and expensive) neighbourhoods in Toronto. In effect, the city-suburb divide is not a construct of class or lifestyle, but of the needs in one’s particular stage of life. In contrast to the apparent one-way “flight” to the suburbs in the United States, it is a round-trip in Canada.(7)

The suburb as the urban

Suburban expansion has long since spilled over the former Metro boundaries into the surrounding regions of Halton, Peel, York and Durham, and beyond. There are now almost twice as many people living in this “outer ring” of suburbs than in the city of Toronto, including the older “inner suburbs” like Don Mills.

The enactment by the Province in 2006 of the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe – Places to Grow (Growth Plan), could be considered the most significant planning intervention in the Toronto region since Metro was established 53 years earlier. The Growth Plan is a deliberate effort by the Province to make and re-make the suburb in the image of the city, in pursuit of “smart growth”: requiring higher densities, a mix of uses, designating new higher-order transit corridors and aspiring to make “people places.”

While there are several, well-intended reasons for the Province to change the growth paradigm – preserving farmland, reducing carbon emissions, promoting healthy lifestyles, etc. – re-making the suburbs in a downtown image is a virtual impossibility due to a combination of market forces and environmental regulations. The establishment of environmental buffer zones from watercourses and other significant natural features, in combination with market forces that prefer larger retail footprints, for example, frustrate the ability to replicate the building typologies and street patterns associated with more intense urban settings (which, it should be noted, have evolved over several decades and in some cases before land uses and building forms were tightly controlled).

Post-suburban prospects for the city-region

The physical, social and economic maturity of Toronto’s suburbs have led to the gradual shift of diversity and political power from the traditional centre to the periphery. Toronto’s infamously embattled mayor, Rob Ford, is the archetype of this shift: hailing from the former inner suburb of Etobicoke, Ford has given a voice to the priorities and sensibilities of residents outside of the central city. Wise to this “suburban ascendancy” provincial and federal parties have made the Toronto suburbs – and suburbs across the country – the new battlegrounds for achieving political supremacy.

The hybridity of Toronto’s suburbs are not only physical, but also temporal. These are places that are both reflecting historic sensibilities the old city and embracing the future through the forging of new typologies. This would appear to support German planner Thomas Sievert’s assertion the suburb “is neither city nor landscape, but which has characteristics of both.”(8)

An argument can be therefore made that the suburbs have become the “new city,” albeit of a completely new sort. The following case studies illustrate examples of new hyburbian developments in the Greater Toronto Area.

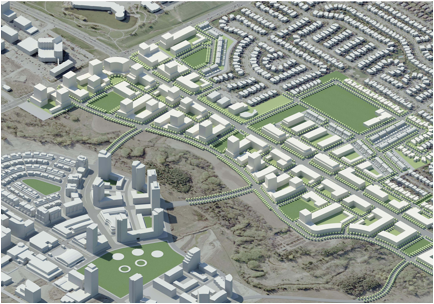

Figure 1: Avonshire Neighbourhood at Yonge & Sheppard Streets. Source: Tridel

Case Study: Shepherd Avenue

Retrofitting a Suburban Corridor

Sheppard Avenue is a major east-west arterial in northern Toronto about 15 kilometers north of the City Centre. Sheppard Avenue connects a series of post-war suburban neighbourhoods across the city. The Sheppard Line is the most recently built subway line of the Toronto subway and was opened in 2002. The 5.5 kilometre long line was the city’s first new subway line since the opening of the Bloor–Danforth line in 1966. The Sheppard Line was intended to relieve highway and transit congestion in the northern part of the city.

Since its construction the Sheppard Line has spurred over $1 billion of construction of dense high-rise developments and new housing along its route. One of the developments involved the assembly of a whole neighbourhood of single-family detached homes to create a large development parcel for an apartment neighbourhood. Other developments included the conversion of large warehouse lands to mixed use apartment neighbourhoods. Recent developments have included mixed-use mid rise projects that infill 1960’s “tower-in-the-park” housing. In total some 14,000 new condo units have been approved, built, or planned.

Despite the urban retrofit of Sheppard Avenue the dense corridor is bounded by a major highway (Highway 401) to the south and suburban postwar one- and two-storey bungalow neighbourhoods directly to the north. The area is framed by two large suburban malls – Bayview Village in the west and Fairview Mall in the east. Limited north-south connections create vehicular congestion along Sheppard Avenue. A decade ago Sheppard Avenue could be characterized as a typical suburban arterial; a bleak suburban streetscape with vast parking lots and buildings set back from the street. Now it is framed with urban buildings along a street jammed with traffic. The people you see on the street are on their way to the subway, and not lingering or visiting cafes.

Figure 2: The Shops at Don Mills (Source: Live at the Shops)

Case Study: Don Mills Centre

A Re-urbanized Mall in the Suburbs

Don Mills Centre is the heart of the Don Mills community located about 18 kilometers from the centre of Toronto. Don Mills was developed in the 1950s to be a self-supporting suburban "new town". At the centre of the community within a ring road surrounding the Don Mills and Lawrence intersection a shopping centre, community centre, curling rink, hockey arena, and other communal facilities were built. An outdoor shopping plaza was opened in 1955 that was later enclosed in 1978. The failing mall was reconceived and was demolished in 2006 to make way for The Shops at Don Mills – a new pedestrian-friendly outdoor shopping mall. The Shops at Don Mills are focused around a town square with a winter skating rink that connected to a grid of pedestrian-focused private streets that are lined with street-related retail shops.

The Shops at Don Mills is a 15 hectare site that is one of the largest retail redevelopment projects in Canada. The redevelopment will increase the total amount of retail and commercial uses on site by 5,000 square metres to approximately 48,000 square metres. The development includes 6,000 square metres of office space, 1,300 residential units in seven buildings and 5,600 square meters of public open space. The resulting mixed-use pedestrian oriented neighbourhood is an urban transformation of a formerly suburban mall surrounded by surface parking lots.

This new urbanized mall sits within a 1950s suburban neighbourhood that is resistant to change. The Shops at Don Mills site surrounded by the four original residential quadrants that are bisected by major arterial roads (Don Mills Road and Lawrence Avenue East). Each quadrant is a distinct residential neighbourhood, centered around an elementary school. The surrounding neighbourhoods are formed by a discontinuous road system of curving streets all ending at T-intersections. Although intended as a pedestrian-friendly neighbourhood many of the streets don’t have sidewalks. Although there are a variety of housing types single-family bungalows predominate. Don Mills Centre is served only by buses along the two arterial roads leaving this new urban mall stranded in the centre of a post-war suburban neighbourhood.

Figure 3: Proposed Langstaff Gateway. Source: City of Markham

Case Study: Richmond Hill/Langstaff Gateway Urban Growth Centre

An Island in the City

The Richmond Hill/Langstaff Gateway Urban Growth Centre is an example of a mid-urban condition on the edge of the City of Toronto 25 kilometers north of Toronto’s City Centre. Connected to the city by a planned extension of the Yonge subway line and an existing commuter rail line, the area is as-of-yet largely a “centre” and “mobility hub” in plan only. One of 25 Urban Growth Centres designated under the Provincial Growth Plan for the Toronto region, the Richmond Hill/Langtstaff Gateway Urban Growth Centre is planned as a high-density and mixed-use transit hub. It is located at the cross-roads of suburban York Region; situated at the intersection of Yonge Street and Highway 7, at the terminus of the planned northern extension of the Toronto Transit Commission’s Yonge Street Subway line. It is a dense, well-connected centre in-waiting. It is planned to achieve a 2031 population of approximately 48,000 and attract 31,000 office and service jobs. Required by the Growth Plan to achieve a density of 200 people/jobs per hectare, the Centre is projected to achieve a density of 675 people/jobs per hectare (which, at full build-out, is highly dependent on the subway extension). This hyper-dense development, although connected at one end to a planned subway station, is so far largely disconnected from the surrounding urban fabric by a major highway and electricity transmission corridor to the north, and a cemetery to the south. The resulting dense 3 kilometer long urban island rivals such integrated urban centres as Yonge and Eglinton and North York in density and population without the flexibility and resilience of a street network that connects to surrounding neighbourhoods. Planning and infrastructure-integration studies have been prepared by the regional and local municipal governments in order to phase development in concert with transportation capacity, and enhanced connectivity (e.g. bicycle lanes) throughout and surrounding the Centre.

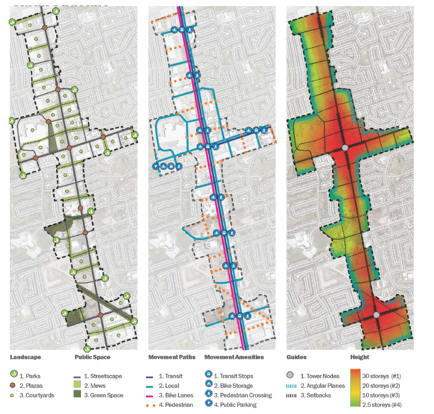

Figure 4: Markham Centre Plans. Source: Sweeny Sterling Finlayson &Co

Case Study: Markham Centre

An Invented City Centre

The City of Markham is directly north of the City of Toronto and about 30 kilometers north of Toronto’s City Centre. Although the City of Markham is comprised of a series of villages that were connected to Toronto by a 19th century rail line Markham Centre was located in an arbitrary manner and is comprised of 364 hectares of largely undeveloped land in the geographic heart of Markham. In the early 1990s Markham Centre was planned to be a brand new downtown for the then Town of Markham complete with a Town Hall surrounded by a mid-rise, mixed-use, pedestrian-oriented and transit supportive urban centre. Markham Centre is projected to ultimately be home to 41,000 residents and 39,000 employees a substantial urban centre for a city of 260,000 people. The area is connected to Toronto by a commuter rail (GO Train) station. A Bus Rapid Transit line will connect the area to other suburban areas to the east and west. A key component of the plan is to transform the central arterial (Highway 7) into an urban boulevard while bringing the BRT south into the centre of the new urban area.

Markham Centre is envisioned to be sustainable urban area. All major developments in Markham Centre are connected to a municipally operated district heat system and will adhere to Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standards. This vision for a sustainable urban area with a highly educated workforce has already attracted leading international corporations such as IBM, Motorola and Honeywell. Markham Centre includes cultural and recreational amenities such as the Markham Theatre for Performing Arts, two secondary schools and a YMCA. Three additional elementary schools are planned to be included in future developments. Markham Centre will ultimately incorporate over 50 hectares of parkland and 78 hectares of open space, including a section of the environmentally significant Rouge River.

Although the area is planned as an urban area defined by an interconnected street grid it is ultimately bounded by a major highway (407) to the south; a major arterial road (Kennedy Road) to the east; a major arterial road (Highway 7) to the north and a collector road (Rodick Road) to the West. Although the street network connects at major intersections across arterial roads, the adjacent neighbourhoods are comprised of post-war dendritic road patterns that are focused on vehicular mobility. The planned centre will function as an urban hybrid: a mixed use, compact, transit-oriented, pedestrian-friendly urban centre surrounded by disconnected suburban morphology.

Figure 5: Vaughan Metropolitan Centre. Source: City of Vaughan

Case Study: Vaughan Metropolitan Centre

A Subway to the Suburbs

Vaughan Metropolitan Centre is a proposed 179 hectare downtown development in the City of Vaughan a suburb of Toronto about 30 kilometers north of Toronto’s city centre. By the year 2031, the Vaughan Metropolitan Centre is intended to accommodate 25,000 residents and 11,000 jobs.

Similar to Markham Centre, Vaughan Metropolitan Centre is planned to be the central business district of Vaughan. The location is arbitrarily located on lands that are predominantly underdeveloped today. It will connect to the Markham Centre and other regional centres to the east and west with a Bus Rapid Transit along Highway 7. Unlike Markham Centre it will be linked by a future subway station to the Toronto subway system. High density employment and residential uses with retail and entertainment establishments will be developed in the area within a 5-minute walk of the subway station.

The vision for the Vaughan Metropolitan Centre is of a vibrant, modern urban centre that incorporates urban amenities including multi-use office towers, residences, parks and urban squares. The sustainable components include a district energy system connecting sustainable buildings that are connected by pedestrian shopping areas, walking and cycling paths.

Vaughan Metropolitan Centre is bounded by major highways to the south and the west (Highways 407 and 400 respectively), a major railway corridor to the east and a major arterial road (Highway 7) to the north. The surrounding lands are predominantly suburban industrial parks. As with Markham Centre, Vaughan’s Metropolitan Centre, as planned, will ultimately result in a dense urban node surrounded by suburban barriers and linked to the city only through high-order transit.

Figure 6: Newmarket Growth Centres. Source: Sweeny Sterling Finlayson &Co

Case Study: Newmarket Growth Centres

An Urban Corridor in the Greenbelt

Newmarket is a town in York Region located 55 kilometers north of Toronto. Although part of the Greater Toronto Area, Newmarket is a small independent city with its own urban centre surrounded by suburban sprawl. The town has a high live-work ratio but is close enough to Toronto to also function as a bedroom community. This small-town/city suburb hybrid nature has recently been evidenced by changes brought by new development pressure.

Newmarket's Yonge Street and Davis Drive Corridors are identified as one of four Regional Centres in the York Regional Official Plan and are recognized by the Provincial Growth Plan as areas where future growth and intensification is to be directed. These corridors are located on the periphery of the town and are predominantly comprised of suburban retail, strip malls, car dealerships and gas stations in addition to a large regional mall (Upper Canada Mall) also positioned behind large surface parking lots. The corridors encompass over 290 hectares of land that include approximately 130 hectares of developable area. There are approximately 30 hectares of planned parks and open space. The Urban Centres have been planned to accommodate 30,000 jobs and 32,000 people by 2031 a very significant growth target for a town of only 80,000 people in a variety of dense mixed-use building forms ranging from townhouses to mid-rise and tower developments. The neighbourhoods are planned for sustainable development and complete communities that emphasize complete streets and transit supportive development. The purpose of the Urban Centres is to accommodate the broadest diversity of uses and the highest quality of design. The new development will be supported by Bus Rapid Transit lines along Yonge Street and Davis Drive.

Surrounding these new urban corridors are low-rise vehicle-oriented suburban neighbourhoods to the east, west and south. To the north is farmland. When fully developed these corridors will dwarf the original downtown in scale and population and create a new linear city that is connected along its arterials by vehicles, Bus Rapid Transit lines and bike lanes.

The recent urban examples described above summarize contemporary development trends in the Greater Toronto Area. The provincial growth plan, the greenbelt around the GTA and transit investments have all contributed to the rapid development of dense urban areas throughout the post-war suburban landscape. Demographics, economics and lifestyle changes have made compact urban neighbourhoods more desirable. As the cost of gas increases millennials choose not to drive and boomers downsize to smaller units. Apartments have overtaken single family houses as the choice of new home ownership. Today there are more construction cranes operating in the GTA than any other North American city including New York and Mexico City. Although these new urban areas are generally well-served by transit they are typically surrounded by low-density single family neighbourhoods or infrastructure barriers. These hybirbian landscapes present new challenges of connectivity and adaptation for the 21st Century as the end of the single-family home emerges.

NOTES AND CITATIONS

[1] Roger Keil, “Global Suburbanization: The Challenge of Researching Cities in the 21st Century” in Logan S., J. Marchessault and M. Propokow, eds., Public 43 (Spring), Suburbs: Dwelling in Transition, 55-61.

[2] Harris, Richard. 1996. Unplanned Suburbs: Toronto’s American Tragedy, 1900-1950. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press.

[3] White, Richard. 2003. Urban Infrastructure and Urban Growth in the Toronto Region, 1950s to the 1990s. Toronto: Neptis Foundation.

[4] Sewell, John. 2009. The Shape of the Suburbs. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

[5] Stewart, Graeme. (No Date). The Suburban Tower and Toronto’s First Mass Housing Boom. Accessed at: http://era.on.ca/blogs/towerrenewal/pdf/AiStewart.pdf

[6] Fishman, Robert. 1987. Bourgeois Utopias. New York: Basic Books.

[7] Lorinc, John. 2008. The New City: How the Crisis of Canada’s Cities is Reshaping Our Nation. Toronto: Penguin Group.

[8] Sieverts, Thomas. 2003. Cities Without Cities: An Interpretation of the Zwischenstadt. London: Spon Press. p. 3

Author’s Biography

Chris Hardwicke

B.Arch, BES, MCIP, RPP

Chris Hardwicke is a Senior Associate of Sweeny Sterling Finlayson &Co Architects, a Registered Professional Planner and an Urban Designer. He is a Fellow of the Urban Design Institute in New York, a Recognized Practitioner in Urban Design in the UK and a member of the Council for Canadian Urbanism. His commitment to city building is internationally recognized through award winning projects such as Velo-city a bicycle highway for Toronto, the Waterfront Master Plan for Kaohsiung, Taiwan; exhibitions at the Dieppe Biennale, the Van Alen Institute in New York; and, publications such as The Good Life: New Spaces for Recreation, and GreenTOpia: Towards a Sustainable Toronto.

Sean Hertel,

MES, MCIP, RPP

Sean Hertel is a Toronto-based consulting planner with experience in policy formulation and development both inside and outside the city. Sean is a Member of the Canadian Institute of Planners, is a Registered Professional Planner in the province of Ontario, and holds a Master in Environmental Studies degree from York University. Sean has conducted academic research on suburban ways of life, and continues that work through his role as Coordinator of the Greater Toronto Suburban Working Group housed at the City Institute at York University.