BRASILE. Dall'architettura sostenibile, una nuova dignità urbana a cura di Carlo Pozzi con Claudia Di Girolamo

torna suIf space is missing, Emanuele Marcotullio

I have to admit, before starting the workshop I was a bit skeptical. A urban regeneration project for an informal city (FAVELAS) in a touristic key (WITH A VIEW), seemed almost heretic.

Among the factors fostering my doubts…the risk of defining the conditions to look at poverty and aestheticize it, the incapacity of registering the real degree of satisfaction of the inhabitants, well matched with the architects’ need to sedate a sort of “natural” anxiety for signs, left on the territory and non-communicated.

I could already imagine groups of Japanese people armed with their flash lights, ready to take a picture of the big architectural object, a beautiful public library, or an efficient cable car station; or middle aged European couples in search of strong sentimentalism strolling around well arranged corners. At the same time I could picture myself seeing the baffled looks of children wondering where those aliens come from and the suspicious reticence of their mothers, ready to shut themselves in their houses looking out from their windows, hidden behind lace curtains.

I have been in a favela a couple of times, and this is what I remember.

Stacked up houses in continuous transformation leave improbable spaces to the activities of the community. Narrow and dusty roads give space to small widening areas for the exchange of goods and services.

Ever open gates, easily-reachable windows and small courtyards are the small-scale demonstration that cohabitation is not an ideological fact but a customary activity consisting of the dwellers’ need and duty to “have neighbors”; all of them forced to re-invent their daily activities and defend them with dignity. Open spaces are remains of the ground, the remains of ways of living that never adulterate the overall image that these villages give of themselves, notwithstanding the extreme instability that characterizes their inner configuration.

Some questions seemed crucial: what to do for tourism without a generous provision of public space? How to solve the problems of a community based on self-planning through the imposition of a strategy that implies the introduction of the foreigner as an economic choice? Does it really make sense to shore up with architectural figures this dense and hectic urban background?

The assigned theme was a challenge: it focused its interest on the relation that a project of spaces created for accommodation purposes can establish between the dwellings and the social practices of a community. It was necessary to understand which touristic production and attraction activities could be proposed and in which spaces; how to build economic synergies and physical relations between these spaces and a tightened and uncertain urban fabric made almost exclusively of houses.

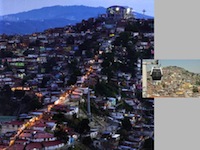

Florianopolis is a bit different from the favelas we are used to remember: the level of decay is not advanced to the point of leading people to despair about their living conditions. Infrastructure systems are guaranteed and houses give an idea of hasty completeness. But it is clear that the transformations of the physical space are the product of transient usages and of the community’s capacity to recognize itself in individual actions without generating conflicts. Everything is written on the houses.

It’s just that space is missing among them. Space is missing to activate regeneration strategies that could introduce in the practices of living also the production of goods and services for accommodation activities. What is missing is a system of relations able to encompass the empty spaces at the small scale of each dwelling and to project them on the background of the spatial resources at a geographical scale.

To work on the fabric of the empty spaces, increasing and extending its links, has become the theme at the center of the project’s experimentation. Through operations of shared micro-demolition, regenerative actions aim at freeing the spaces necessary to introduce – around dwellings – an additional provision of public space to be used for accommodating purposes: areas for small markets, spaces for concerts or artistic performances, gardens, laboratories for the production of local products, and also shared systems of restoration and accommodation.

“To free space” means identifying together with the community all the spaces that the transformation of family needs has made unnecessary, in addition to those that each family chooses to make available; it means defining the physical conditions necessary to activate, at a local level, the free initiative of those inhabitants ready to bet on the touristic market. Ideally through the long-term transformation of other domestic spaces.

The project’s outcome is thus the representation of a method, rather than a well-shaped frame of spatially identified actions. The text written by Professor Coccia well describes the instruments used and the goals reached.

As a marginal note, I only have one comment: to make proliferate around dwellings spaces of intermediate nature means to propose a reflection on new ways of living that somehow impose also a re-thinking of the operational instruments; it means to endow the project with the double value of being a concrete answer to urban problems and of being, at the same time, a process able to impact dwellers’ awareness.

In a closed and very dense context such as the one of Florianopolis, the contribution that each dwelling’s private space can offer to the definition of public micro-spaces is simply unavoidable. These “anarchical” spaces can help integrate the map of the “public” space necessary for the local community to maintain in constant work a form of self-government and to provide new approximate orders resulting from heretic practices.