The History of Ljubljana from Prehistory to Modern Times

Breda Mihelič

Breda Mihelič

Archaeological evidence shows that the Ljubljana Basin was already settled in prehistoric times, when the ancient Amber Road and other trade routes between the Baltic Sea, the Balkans and the Italian Peninsula led through the Ljubljanska vrata (Ljubljana Gate). Archaeologists have found evidence of pile‑dwelling settlements from the end of the Neolithic in the Ljubljansko barje (Ljubljana Marsh) and remnants of the oldest settlement in what is now Ljubljana on Grajski grič (Castle Hill).

Roman Emona

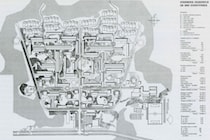

Prehistoric routes also influenced the colonisation of the Ljubljana Basin during the Roman era. Along the main route that connected the eastern and western part of the Roman Empire, a Roman settlement called Colonia Iulia Emona was built under Emperor Augustus between AD 14 and 15 in what is now Ljubljana. This is proven by an inscription found in 1887 in today’s Trg francoske revolucije (French Revolution Square). It was probably built into the wall above the eastern city gate and it now forms part of the collection of stone monuments displayed at the Narodni muzej (National Museum) in Ljubljana. The city was built following the model of Roman castra (legionary encampments). It had a rectangular layout and was protected with six‑metre walls like a fortress. Emona existed until the mid‑sixth century, when it was conquered by the Ostrogoths, who destroyed the city, and its name gradually slipped into oblivion.

Part of the southern Roman wall and the northern city gate (today’s Slovenska cesta, Slovenia Street) have been preserved, and the remnants of an early Christian centre and a Roman house are displayed in situ in two outdoor museums. The Roman legacy is also evident in the rectangular street network in the western part of the city centre. The heritage of the two main Roman streets, the cardo maximus and the decumanus maximus, are present‑day Slovenska cesta (Slovenia Street) and Rimska cesta (Rome Street).(fig.1)(fig.2)(fig.3)(fig.4)(fig.5)

Medieval Ljubljana

Ljubljanski grad (Ljubljana Castle) was first mentioned as Leibach in an Aquileian document from 1112–1125 that was found at the Chapter Archive in Udine, Italy. It is mentioned in connection with a lawyer by the name of Rudolf, who donated twenty farms around Ljubljana Castle to the Church of Aquileia. The medieval city below the castle was established in the twelfth century by the Carinthian dukes of the House of Spanheim. The city arose next to the ruins of the former Roman town and was protected by the castle and the Ljubljanica River. It was elevated to the capital of Carniola as early as the mid‑thirteenth century. At that time, three core settlements already existed below the castle: at Stari trg (Old Borough), Mestni trg (Town Borough) and Novi trg (New Borough). They were surrounded by walls that connected them to the castle. Five gates led into the city and the entry along the Ljubljanica River was protected by the Vodna vrata (Water Gate), also known as grablje (the trash rakes). All three core settlements were also connected by a gate. Despite later modifications and expansions, the medieval city layout in the shape of a half‑moon wrapped around Castle Hill has been preserved to the present day.

In 1335, the city was conquered by the Habsburgs, who continued to rule the Slovenian lands until the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy after the First World War. During the nearly six hundred years of Habsburg rule, Ljubljana was a relatively small and insignificant provincial capital of Carniola. Nonetheless, it generated many important figures that shaped European social, scientific, cultural and art history, and whose names are often used to refer to individual stages of the city’s development.

Trubar’s Ljubljana

In the sixteenth century, Ljubljana was a centre of Protestantism. The key figure was Primož Trubar, a Protestant clergyman, translator and author of the first two Slovenian printed books (i.e., Catechismus and Abecedarium, 1550), with which he laid the foundations for the development of standard Slovenian. Thanks to the Reformation movement, a church‑run Latin school, the first printing house and the first public library were established in the city. In terms of art, this was the Renaissance, which did not leave any major traces in the city. The castle’s residential structures were built and some houses owned by wealthier town residents and nobility were renovated in the Renaissance style, and the city obtained new, continuous street fronts. In 1654, the Austrian military engineer Martin Stier designed plans for new city walls following the model of Renaissance city fortifications. However, the walls were not built because in the meantime the immediate threat of Ottoman attacks had ceased to exist.

Baroque Ljubljana

The beginning of the Baroque period was linked to the Counter‑Reformation and the Catholic restoration. The Jesuits, who settled down in the city around 1600, built the first Baroque church (i.e., Cerkev svetega Jakoba, St. James’ Church) following the model of the Chiesa del Gesù (Church of Jesus) in Rome. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, during the Baroque period, the city experienced significant cultural and artistic progress and was thoroughly renovated in the Baroque style. The most credit for this went to the Academia operosorum Labacensis (Academy of the Industrious), which was established in 1693 following the model of modern Italian academies. Its members were strongly committed to the development of science and the arts. The circle of academy members, among whom the brothers Anton and Gregor Dolničar were especially active, provided the impetus for the construction of a new cathedral and episcopal seminary, and the renovation of the town hall. At the academy’s invitation, a number of important Italian artists, such as the architects Andrea Pozzo, Carlo Martinuzzi and Candido Zuliani, the sculptors Angelo Pozzo and Francesco Robba, and the painter Giulio Quaglio, took part in the city’s Baroque renovation, converting Ljubljana into the Slovenian centre of Baroque art by the end of the century. Thanks to these artists, the town square with its Vodnjak treh kranjskih rek (Fountain of the Three Carniolan Rivers) in front of the town hall became one of the most beautiful Baroque sites in central Europe. In the suburbs outside the city walls, various prominent structures were built based on the designs of Italian architects, such as the Franciscan and Ursuline churches (Carlo Martinuzzi), St. Peter’s Church (Giovanni Fusconi), Visitation Church on Rožnik Hill (Candido Zulliani) and a number of attractive houses for the nobility and wealthier town residents.

Valvasor’s Ljubljana

In the second half of the seventeenth century, Johann Weikhard von Valvasor (1641–1693), a historian, geographer, cartographer, scientist, collector, draftsman, publisher and member of the London Royal Society, rose to local and international scholarly prominence. In his Topographia Archiducatus Carinthiae antiquae et modernae completa (Topography of the Duchy of Carniola, 1688), he published 320 copperplate engravings of Carniolan towns, market towns, monasteries and castles, and in his Die Ehre deß Hertzogthums Crain (The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola, 1689), which was the first systematic presentation of Slovenian history, territory and lifestyle, he described in detail and graphically presented the Ljubljana of that time. His bird’s‑eye‑view drawings of the city and graphic presentations of the street fronts still serve as the basis for the city’s urban and architectural history at the end of the seventeenth century.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, Anton Tomaž Linhart from the Enlightenment circle continued Valvasor’s research on Carniola in his Versuch einer Geschichte von Krain und den übrigen Ländern der südlichen Slaven Österreiches (An Attempt at a History of Carniola and Other South Slavic Lands of Austria, 1788 and 1791), but he did not finish the book.

Napoleon’s Ljubljana

During the Napoleonic Wars, Ljubljana was the seat of the governor‑general and the capital of the Illyrian Provinces from 1809 to 1813. The Illyrian Provinces spanned the area between the Hohe Tauern (High Tauern) in today’s Austria and the Bay of Kotor in today’s Montenegro. The short‑lived French annexation encouraged the development of the city and Slovenian culture. The French introduced Slovenian into the administration, the school system and cultural life in the city. They established the first École centrale (university college) and a botanical garden along Ižanska cesta (Ig Street) as part of it. The French also introduced the idea of a green city to Ljubljana. They planted the first tree‑lined avenue along the Ljubljanica River behind the high school on Vodnikov trg (Vodnik Square), and their engineer Jean Blanchard designed the plans for the Tivoli Park avenues, which were planted by the Austrians after they recaptured the city.

Prešeren’s Ljubljana

After the French defeat, Ljubljana again became part of Austria and now remained only the provincial centre of Carniola and Carinthia. It re‑entered international history in 1821, when it hosted the Congress of the Holy Alliance (i.e., the coalition of countries that defeated Napoleon), which was attended by the most important European sovereigns (Austrian Emperor Francis I, Russian Tsar Alexander I, Ferdinand IV of Naples and Francis IV of Modena) and around 500 ministers and other political representatives of the participating countries.

The first half of the nineteenth century is connected with the personality of France Prešeren (1800–1849), the Romantic Slovenian poet that elevated Slovenian literature to a comparable international level for the first time in history. His collection of poems Poezije (Poems, 1847) places him at a level alongside the great European poets, such as Karel Hynek Mácha among the Czechs and Adam Mickiewicz among the Poles. This was the period of great social changes, national conflicts, the development of national awareness among the intelligentsia, and interest in linguistic, ethnographic and historical issues, which ended with the 1848 March Revolution and the fall of Metternich’s absolutist government.

In general, until the mid‑nineteenth century Ljubljana’s economy was poorly developed. The city had only three major industrial plants (two sugar refineries and a cotton mill). In the early nineteenth century, the city began to grow beyond its old, formerly walled town core. New streets were built where the former city walls and moats used to be, new squares were laid out at the location of the former city gates, and new quays were constructed on the banks of the Ljubljanica River. However, it was only the railway – built in 1847 from Vienna to Ljubljana, and from Ljubljana to Trieste ten years later – connecting the city with the rest of the world that accelerated the exchange of people and new ideas, and stimulated the city’s economic development.

Industrial Ljubljana

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the city began to grow more quickly. However, the statistical data show that, even in 1900, the city had only 36,547 residents, which was hardly more than a large district in Vienna. It lagged behind Trieste, Graz, Linz, Pilsen and even Pula in terms of population (i.e., behind cities that it significantly surpasses today).

Urbanisation began in the areas between the old suburbs and the railway. The land in the western part of the city was purchased by the Kranjska stavbna družba (Carniolan Construction Company, founded in 1873), which designed an urban development plan and built up most of this land by the end of the century. Among other things, the building of the Kranjska hranilnica (Carniolan Savings Bank), the Deželni muzej (Provincial Museum), and many other modern residential houses and mansions were built according to this company’s designs. In 1888, the city building department designed an urban development plan for the northern part of the city between the Šempetrsko predmestje (Saint Peter District) and the railway station, but the construction work only began after the 1895 earthquake.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, important industrial facilities (e.g., a brewery, a tobacco factory, a slaughterhouse, machine factories and foundries) and infrastructure (e.g., the city gasworks, power plant, the city water supply system and the city tree nursery) were also built in the city. Ljubljana also got a street lighting system, its streets began to be paved, public baths were established, waste collection was set up, and in 1901 the first city tram line connected the main railway station with the railway station on Dolenjska cesta (Lower Carniola Street). All of this contributed to greater economic importance of the city, better health conditions and hygiene, and greater prominence.

Nonetheless, up until the end of the nineteenth century, Ljubljana retained a more rural appearance. It was only the earthquake that devastated the city in 1895 that provided the real impetus for modern urban development. It destroyed more than one‑tenth of the houses and heavily damaged most of the rest. With major financial support from the entire monarchy, the city recovered in a relatively short time and began changing rapidly and acquiring the attributes of a modern national capital.

Three periods of modern urban planning in Ljubljana

The modern development of the city in the twentieth century was closely connected with three key architects: Max Fabiani (1865–1962), Jože Plečnik (1872–1957) and Edvard Ravnikar (1907–1993). Their names are often used to refer to individual stages of the city’s modern development.

Fabiani’s Ljubljana

As an Austrian provincial centre, Ljubljana was politically, economically and culturally strongly attached to the imperial capital up until the end of the First World War. Vienna was the fourth‑largest city in the world, the capital of the monarchy and the largest commercial, industrial, university and arts centre that influenced all areas of the social, political, economic, cultural and artistic life in the entire monarchy. Vienna attracted people from all over the monarchy and especially students because a degree from the University of Vienna was a guarantee for a successful career.

Many Slovenians also studied in Vienna because, despite nearly half a century of efforts, Slovenia did not receive its own university until the end of the First World War. Medical and law students predominated, and writers and painters among the artists. The first Slovenian architecture students in Vienna were Max Fabiani, Janez Jager, Jože Plečnik and Ivan Vurnik. Plečnik and Fabiani also reached the apex of their careers there and are ranked among the most important representatives of Vienna modernism.

After the Easter earthquake of 1895, the city council headed by Mayor Peter Grasseli immediately began developing a large‑scale reconstruction plan for the city, which also entailed the production of a general urban development plan. At the proposal of the Society of Engineers and Technicians in Vienna, the council invited one of the most prominent Viennese urban planners at that time, Camillo Sitte, to prepare the plan. In 1889, Sitte wrote the book Der Städtebau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen (City Planning According to Artistic Principles, 1889), which had an exceptional impact on the urban planning of Austrian cities around 1900. In it, he advocated a culturalist and aesthetic approach to urban planning, which he believed was typical of preindustrial, especially medieval and Renaissance, towns, and criticised “bloodless, anaemic and agoraphobic modernisations” subordinated to traffic needs.

Max Fabiani also submitted his own draft urban development plan to the city council after the earthquake. At that time, Fabiani was working on the project for the tram system in Vienna together with Otto Wagner, who was known for his progressive urban planning ideas. Wagner emphasised that, first and foremost, planning must follow the requirements and needs of modern times, and his personal motto was artis sola domina necessitas (necessity is the only master of art). Fabiani helped Wagner with his theoretical work; he helped him write the book Moderne Architektur (Modern Architecture, 1895) and at Wagner’s request wrote the editorials for the first two issues of Aus der Wagner Schule (From Wagner’s School), which was published from 1895 to 1910 as a supplement to the journal Der Architekt (The Architect).

Fabiani supported Wagner’s ideas, and he used and reworked them in his urban designs, and especially in his urban development plan for Ljubljana and the Polish town of Bielsko. Like Wagner, he considered the beauty of a city to be a perfect harmony of form and function, and emphasised that in urban planning it is absolutely necessary to “pay equal attention to aesthetic and practical issues.” On the other hand, he agreed with Sitte, whom he highly respected, that a city is a pure work of art, in which the architect and urban planner must take into account the local traditions (genius loci), even though they want to be modern. In the introduction to his book Vicenza, Fabiani wrote: “We have surpassed our ancestors in terms of principles, professional skills and expertise, but we will still have to learn from them about the beauty of expression for a long time, if not even forever.”

Fabiani’s draft urban development plan of Ljubljana can be understood as a synthesis of Sitte and Wagner’s urban planning ideas. In this plan, Fabiani combined Sitte’s method of the morphological analysis of the city with Wagner’s planning principles and, what is most important, he treated the city in three dimensions. He strove to preserve the city’s character that had been shaped through history. “I have in principle adapted anything that I changed in squares and roads to the city’s traditional character as far as I could,” he wrote in the report accompanying his draft urban development plan for Ljubljana.

The framework of his urban development plan consists of the castle with Castle Hill as a focal point towards which the main radial roads run, and two concentric streets arching on both sides of the Ljubljanica River along which the major town squares are laid out. Fabiani expanded this framework by extending some radial roads all the way to the city centre and by designing a new ring road or a wide boulevard on the edges of the built‑up city along the railway, following the model of the Ring road in Vienna. He envisioned prominent public buildings along this ring road.

The official urban development plan that was designed by the city engineer Jan Duffé on a commission from the municipal council took into account the majority of Fabiani’s ideas, which were more adapted to the city’s character and needs than those of Sitte.

The section of the ring road between Prešernova cesta (Prešeren Street) and Masarykova cesta (Masaryk Street) was constructed based on Fabiani’s plan. Sixty years later, his plan was used to connect Zoisova cesta (Zois Street) and Dolenjska cesta (Lower Carniola Street) through Rožna ulica (Rose Street). More than a hundred years later, Roška cesta (Rog Street) and Njegoševa cesta (Njegoš Street), which Fabiani envisaged as part of the inner ring road, were connected. During the interwar period, Jože Plečnik used Fabiani’s urban development plan as a basis for modifying the urban fabric.

Fabiani’s draft urban development plan is considered the first modern urban development plan of the city. The report accompanying the plan, which Fabiani published in the form of a booklet, was the first technical text on urban planning in Slovenian. With it, Fabiani laid the foundations for Slovenian urban planning terminology.

On a commission from the Municipality of Ljubljana, Fabiani also designed the square in front of the courthouse. He designed it as a slightly elevated platform oriented towards the courthouse front, paved in a combination of asphalt and white stone, and flanked on two sides by a double tree‑lined avenue. He suggested that several statues or excavated monumental Roman fragments from the National Museum’s yard and basement should be placed on the platform. He also envisaged surrounding uniform buildings of the same height accentuated with corner towers resembling those in Prague, which was the idea of Ljubljana Mayor Ivan Hribar. He designed the house on the corner of Tavčarjeva ulica (Tavčar Street) and Miklošičeva cesta (Miklošič Street) for the Ljubljana lawyer Valentin Krisper, which provided the model for all the other buildings around the square: the Regallijeva hiša (Regalli House) to the south and the residential buildings on the west side of the square that were built based on designs by the city architect Ciril Metod Koch. The square was built up from three sides in less than ten years. The south side was partly closed off after the First World War by the Vzajemna zavarovalnica (Mutual Insurance) Building (1922) and only completely closed off after the Second World War with the Dom sindikatov (Trade Union House) designed by architect Edo Mihevc (1966).

After the earthquake, Fabiani also designed some other important buildings in Ljubljana, such as the Bambergova hiša (Bamberg House on the southeast side of Miklošičev park (Miklošič Park), Mayor Hribar’s house along Slovenska cesta (Slovenia Street), St. James’ rectory on Gornji trg (Upper Square) and the girls’ high school on Prešernova cesta (Prešeren Street). At the initiative of the painter Rihard Jakopič, he designed the first Slovenian art gallery and painting school in Park Tivoli (Tivoli Park), which provided a home to Slovenian artists up until the 1960s, when it was demolished due to relocating the railway line. Fabiani’s Ljubljana oeuvre shows his artistic development from pure Vienna Secession (the Krisperjeva hiša, Krisper House) to modernism (the Bambergova hiša, Bamberg House, Mladika), which already indicates a transition to a new, functionalist phase of architectural development.

The city also expanded administratively after the earthquake. In 1896, the Vodmat District came under its administration, and in 1905 the Municipality of Ljubljana purchased Ljubljana Castle, which was previously owned by the provincial government. Construction was carried out in the suburbs between the old town and the railway, and the municipality also began planning the city’s expansion north of the railway. In 1898, it commissioned an urban development plan for this area from Max Fabiani. Following Wagner’s model of the Vienna districts, Fabiani designed it as an autonomous city district with all the necessary infrastructure and services that ensured its independent functioning. He directed the main line of this new city district, the radial road leading to the new cemetery at Cerkev svetega Križa (Holy Cross Church), towards the castle, and designed a large square with a church, school and swimming pool as the centre at the intersection of the radial and diagonal roads. He connected the district with a rectangular network of streets that narrows a little towards the city, with diagonal roads linking important points. He connected the streets of the new part of the city north of the railway with the streets of the old town south of the railway. Fabiani was among the first to draw attention to the fact that the railway would have to be removed or rearranged through grade separation because it represented an obstacle to city development.

In addition to Fabiani, a number of architects from Vienna, Graz, Budapest and other parts of the monarchy also helped with the post‑earthquake reconstruction of Ljubljana. They built important public and residential buildings in the new parts of the city. Many architects from various Slavic lands, such as Bohemia, Moravia, Croatia and Dalmatia, were invited to the city by the municipality and Mayor Ivan Hribar, an ardent supporter of the pan‑Slavic movement. Some of them even found employment with the Municipality of Ljubljana (e.g., the architects Jan Duffé and Jan Vladimir Hrásky, and the city gardener Vaclav Heinic). It was also thanks to all of these architects that a new style (i.e., Secession) became established in Ljubljana after the earthquake, giving an art nouveau character to the architecture of the entire quarter between the old town and the railway line along Miklošičeva cesta (Miklošič Street) and Miklošičev park (Miklošič Park. The best examples of Secession buildings were built here in the first decade of the twentieth century, including the first modern department store by Friedrich Sigmundt (1903), the first modern hotel by Josip Vancaš (1903–1905) and important banking institutions, such as the Mestna hranilnica (City Savings Bank) and the Ljudska posojilnica (People’s Loan Bank) by Josip Vancaš, and the Zadružna gospodarska banka (Cooperative Bank) by Ivan Vurnik after the First World War, as well as a number of residential buildings.

A year after the earthquake, new building regulations for Ljubljana were adopted, which defined the width of the new streets, the construction and the building heights for individual areas of the city. By the First World War, the city inside the ring road planned by Fabiani had already been largely built up.(fig.6)

Plečnik’s Ljubljana

After the First World War, when Slovenia became part of the new Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia), Ljubljana became the administrative and political centre of Slovenia. The links with the former capital were more or less broken, especially when a Slovenian university was established in Ljubljana in 1919, which made it possible for Slovenians to study in their home country. The university comprised the faculties of theology, law, arts and technology, and a preparatory faculty of medicine. An especially important role was played by the school of architecture that was established as part of the Faculty of Technology at the initiative of architect Ivan Vurnik. He invited Max Fabiani and Jože Plečnik to teach there. Fabiani declined the offer because he decided to return to the Gorizia region after the war to help with post‑war reconstruction, whereas Plečnik accepted the invitation and returned from Prague to work as a professor at the school. His class followed the model of Wagner’s school in Vienna. He predominantly discussed artistic, aesthetic and spatial‑plastic issues of architecture with his students. In contrast, Vurnik focused more on technical issues of architecture and on the problems of residential architecture, and he also introduced urban planning as a university course. In 1929, the first class of Slovenian architects graduated from this school. Before the Second World War and especially after it, these graduates took on important architectural and urban planning tasks.

With his urban projects and unique architecture, Plečnik left the most important mark on interwar Ljubljana. He was Otto Wagner’s student and worked with him in his studio for a while. Just like Fabiani, Plečnik knew Wagner very well and his proposal for Vienna’s expansion, as well as with his theoretical studies on architecture and cities. Wagner held Plečnik in high esteem and even proposed him as his successor at the school of architecture, but his Slovenian roots prevented his appointment in the context of ethnic tensions before the First World War.

After returning to Ljubljana, Plečnik worked closely with the head of the city building department, Matko Prelovšek, on the city’s renovation and construction. At Prelovšek’s initiative, he designed a draft urban development plan of Ljubljana in 1926. Namely, after the First World War, Ljubljana grew rapidly and expanded towards the area beyond the railway. Urbanisation even expanded to the nearby villages, which became an administrative part of the city in the early 1930s. Plečnik himself wrote that he based the plan on existing projects for individual parts of the city, which he expanded with his own suggestions for detailed designs of squares and urban areas, especially inside the railway ring. He envisaged Ljubljana as a compact city within a ring road that he placed far beyond the built‑up area of the city, around the newly incorporated villages and Rožnik Hill. Following Wagner’s model of a metropolis, he envisaged the new settlements within this ring as semi‑autonomous urban quarters outfitted with all of the necessary public facilities and infrastructure, and used radial roads to establish good connections with the city centre. As a case study, he created a detailed plan for the Svetokriški okraj (Holy Cross District) or the southern part of what is now the Bežigrad neighbourhood, as a typical residential quarter for 30,000 to 40,000 residents. He designed the street network in the shape of a fan that narrows down towards Dunajska cesta (Vienna Street) and connects it with the city centre. He placed the centre of this quarter along a wide monumental avenue connecting the cemeteryby Cerkev Svetega Križa (Holy Cross Church) with Dunajska cesta (Vienna Street). He envisaged a theatre, district administrative office, church and school along this avenue. The quarter was to be built up with mansions and apartment buildings surrounded by green areas. The provincial administration approved Plečnik’s plan in 1930. Despite later changes, this part of the city developed up until and even after the Second World War more or less based on his plan.

On a commission from Matko Prelovšek, Plečnik designed a series of extremely beautiful urban spaces in the inner city inside the railway ring, linked along several axes: for example, a “green avenue” along the axis running from the Cerkev svetega Janeza Krstnika (Saint John the Baptist Church in Trnovo) to Južni trg (South Square), and the route to the castle running from Zoisova cesta (Zois Street) via Levstikov trg (Levstik Square); along the Ljubljanica River he developed the quays on both sides of the Prule neighbourhood to the sluice near the sugar refinery and connected them with new bridges across the river.

Plečnik designed the section between the Trnovo church and Južni trg (South Square) as a dynamic sequence of intimate public spaces in a vibrant dialogue between natural and artificial elements, and between the old and new; he reshaped these spaces with simple architectural and natural elements, such as trees, memorial plaques, statues, fountains, lights and so on. This is how he created new urban spaces, axes and views. He designed the bridge across the Gradaščica River in front of the Trnovo church as a square and planted it with trees. He placed an Illyrian pillar on Trg francoske revolucije (French Revolution Square), remodelled the walls of the Monastery of the Teutonic Knights and added windows to them, and placed a statue of Simon Gregorčič below a wooden pergola on the opposite side. He designed a maple‑lined avenue on Vegova ulica (Vega Street) and a raised longitudinal park on the foundations of the medieval walls on the east side, in the area between the university library and the university building. He placed herms of Slovenian composers on the edge of the park in front of the Glasbena matica (Music Society) building. He repaved Kongresni trg (Congress Square), moved the statue of the Holy Trinity from the Ajdovščina neighbourhood to in front of the Uršulinska cerkev (Ursuline church) and designed a raised platform with a balustrade in front of the church. He placed a weather house at the end of Vegova ulica (Vega Street), and a statue and a fountain in Park Zvezda (Star Park).

Plečnik designed a monumental square inside the urban block between Slovenska cesta (Slovenia Street), Čopova ulica (Čop Street), Wolfova ulica (Wolf Street) and at the end of the “green avenue”. Like a Greek agora, it would be the new centre of Ljubljana intended for public urban life and public events. He envisaged a monumental entrance to the square in the form of propylaea, under which he planned to place an equestrian statue of King Alexander in 1937. This plan as well as his plan for Južni trg (South Square) was never executed. Nonetheless, ideas of setting up a square in this area in one form or another are still alive.

Architect Dušan Grabrijan recognised a desire in Plečnik’s project of the “green avenue” to create something magnificent in Ljubljana, something that he admired in the Paris of Louis XIV or the Rome of Pope Sixtus V. As shown by Plečnik’s letters, the Renaissance and Baroque art that he got to know during his travels in Italy and France had truly made a great impression on him. Grabrijan even recognised specific parallels with the distinctive Parisian cityscape, from Place de l’Étoile (Star Square) via Avenue des Champs‑Elysées (Elysian Fields Avenue) and the Tuileries Palace to the Louvre, in Plečnik’s plan, which was of course adapted to the scale of Ljubljana at that time.

Plečnik connected Zoisova cesta (Zois Street) and its faculty of architecture with the route to the castle. He planted oaks and maple trees along the street, he rearranged the walls of the Monastery of the Teutonic Knights, built an old door frame and the memorial plaque from the razed Smoletova hiša (Smole House) in the Ajdovščina neighbourhood into the monastery walls at the end of Križevniška soteska (Teutonic Knights Alley), and added a raised longitudinal park in front of the walls and the backs of houses along Križevniška ulica (Teutonic Knights Street). He placed a pyramid along the axis between the end of Zoisova cesta (Zois Street) and Šentjakobska cerkev (St. James’ Church) as a monument to the industrialist, natural scientist, Maecenas and man of letters Sigismund Zois (1747–1819). He separated the square in front of the church from the road with spherical concrete bollards and low, round maple trees, and placed a fountain and a statue of Mary on a 9.5‑metre pillar on the square. He designed a new facade for Cerkev svetega Florijana (St. Florian’s Church) at the beginning of Ulica na grad (Castle Street), moved its main entrance, and built a set of steps and a landing in front of it. From here he paved the street anew with decorative stone and trees planted alongside the street. Plečnik planned to turn the castle into the central city monument and proposed adding a new tower to the castle building and converting the castle into a museum. After the war, he envisaged the new Slovenian parliament on Castle Hill, which would be connected to the city with monumental stairs behind the town hall and a scenic path leading up from the cathedral.

Plečnik also reshaped the banks of the Ljubljanica River between the Trnovo neighbourhood and the sluice gate next to the old sugar refinery building, and connected both riverbanks with new bridges. He built the Čevljarski most (Cobbler’s Bridge) where the old Mesarski most (Butcher’s Bridge) used to stand and designed it as a large square covered with a pergola – which, however, was never built. He added two separate pedestrian bridges to expand the oldest bridge that led to the walled city from today’s Prešernov trg (Prešeren Square) and had become too narrow due to increasing traffic. All three bridges together function as a funnel‑like square before the entrance into the old town. He designed steps on both lateral bridges leading down to the river banks, which he turned into a promenade. He added balustrades to all three bridges, which gives a Venetian flair to the whole.

Plečnik designed market halls on the left bank of the Ljubljanica River between the Tromostovje (Triple Bridge) and the Zmajski most (Dragon Bridge). On the river side, the market halls indicate where the city walls used to run, and on the inner side they close Vodnikov trg (Vodnik Square) towards the river in the form of a monumental classical colonnade. He left room in the centre for a new covered bridge that would connect Vodnikov trg (Vodnik Square) with Petkovškovo nabrežje (Petkovšek Quay) and Kolodvorska ulica (Railway Street) further up via Prečna ulica (Transverse Street). However, instead of this, a modern bridge designed by architect Jurij Kobe was built here in 2012.

Even though Plečnik did not carry out all of his ideas in Ljubljana, he nonetheless managed to connect the artistic heritage of the previous centuries and give the city a personal touch, just like a painter gives one to his canvas or a sculptor to his statue. Therefore, “Plečnik’s Ljubljana” is a synonym for the city that developed during the interwar period. “His work can be admired in every square, on every street corner and in every park in Ljubljana because its gives the structures and their surroundings a characteristic look . . . . Plečnik’s name already radiates beyond the borders of his home country, but it must achieve increasing recognition throughout the world because he should be ranked among the best of his period,” which happened only at the end of the twentieth century.

Other architects were also active in the 1930s in addition to Plečnik. They followed more modern directions in architecture and urban planning under the influence of German functionalists, Le Corbusier and the CIAM (Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne, International Congress of Modern Architecture). An important role in this regard was played by Ivan Vurnik, who was already focusing on modern functionalism by the second half of the 1920s (the Kopališče Obla gorica, Round Mountain Pool, in Radovljica), explored new forms and types of residential architecture (the working‑class residential area in Maribor), wrote about this and delivered talks on urban planning. Plečnik’s younger students were also increasingly interested in the modern movement, especially after they visited the L’Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes (International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts) in Paris in 1925 and saw Le Corbusier’s pavillon de l’Esprit nouveau (Pavilion of the New Spirit). Under the influence of modern Austrian and German architecture, and the CIAM, a completely new quarter of functionalist mansions and residential buildings was built in the Vrtača neighbourhood (Josip Costaperaria, Vladimir Šubic), and large social residential buildings, suchas the Meksika and the Delavska zbornica (Chamber of Labour) buildings (Vladimir Šubic, 1922 and 1927–1929), and the Rdeča Hiša (Red House, Vladimir Mušič, 1927–1929), were built following the model of the Höfe (large‑scale Vienna social housing). A new central business district with the first skyscraper as a symbol of the city’s interwar prosperity was built along Slovenska cesta (Slovenia Street) by Vladimir Šubic (1933).

The links between Yugoslav architects grew stronger during the interwar period. From 1931 to 1934, Slovenian, Croatian and Serbian architects published the journal Arhitektura (Architecture). A number of Slovenian architects and designers, and their Croatian and Serbian contemporaries, the majority of whom had earned their degrees outside Yugoslavia, published their works in it. The journal also reported on developments in architecture and urban planning abroad as well as on new books and journals published abroad. The journal was even mentioned as the reference journal for architecture and urban planning in Yugoslavia in the French journal L'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui. In general, connections with France were very close in the 1930s. In 1931, young Yugoslav architects participated at the international exhibition of modern architecture in Paris, and some of them, including Edvard Ravnikar and Marjan Tepina, even worked in Paris towards the end of the 1930s.

Young Slovenian architects already had the opportunity to test new ideas before the war, when competitions for the design of Prešernov trg (Prešeren Square, 1935) and Kongresni trg (Congress Square, 1937) were announced, and especially in 1939, when the Municipality of Ljubljana announced the competition for designing an urban development plan for Ljubljana.

Ravnikar’s Ljubljana

Edvard Ravnikar was among the nine Slovenians that worked in Le Corbusier’s studio on Rue de Sèvres (Sèvres Street) in Paris for a few months before the Second World War. He played the most important role in Ljubljana’s architectural and urban‑planning development in the second half of the twentieth century. Ravnikar was a student of Jože Plečnik, was highly educated, and was active in a range of fields, from urban planning, architecture, design and painting to theoretical research, journalism and teaching. He worked as a professor at the University of Ljubljana’s Faculty of Architecture from 1946 until his retirement in 1980. He taught the most important Slovenian architects from the second half of the twentieth century. The key ideas and concepts of post‑war urban planning and architecture were created and developed in his classes, as well as the most important architectural and urban‑planning projects that changed the image of Ljubljana and other Slovenian and Yugoslav cities.

The experience of working in Le Corbusier’s studio left a strong impression on Ravnikar and influenced his work before and especially after the war. He first used Le Corbusier’s ideas in his entry for the competition for the urban development plan for Ljubljana (1939), in which many other young architects also participated. In line with Le Corbusier’s urban‑planning principles, in his design proposal Ravnikar systematically divided urban areas according to their predominant functions into a city centre built as a city‑in‑the‑park, residential areas north of the railway built up largely with long narrow apartment buildings and industrial zones along the railway lines. He proposed running a motorway through the city centre, splitting it into two branches in the form of a double Y in the north and south. He extended the green recreation areas between the corridors to the city centre itself and surrounded the city with an outer ring road. After the war, Ravnikar further developed his concept of a star‑shaped city, which even today continues to serve as the basis for urban spatial development.

The key renovation and construction projects in the city after the war were carried out by a group of young architects, headed by Ravnikar. Even though they first had to tackle completely new architectural and urban‑planning tasks, after the war the young architects continued to develop the ideas and projects that they had started before the war. Socialist realism did not have a decisive impact on architecture and urban planning in Yugoslavia. After the war, architects remained in contact with international development and with architects in other countries. As Ravnikar wrote in 1950, “after the liberation a new period of urban planning began . . . the urban‑planning work passed to younger architects that advocated more progressive views on the discipline immediately before the war. What was regarded as utopian and unrealistic before the war has now been completely legalised.” That same year, architects attended the conference of the Union internationale des Architectes (International Union of Architects or UIA), and during the 1950s they presented their works at a number of exhibitions in Oslo, Copenhagen, Warsaw, London, Liverpool and Glasgow, and at various international fairs. In 1956, they also hosted a CIAM conference in Dubrovnik, which was an important recognition for them. They kept abreast of developments abroad indirectly via foreign journals and newspapers, and through direct contacts with recognised foreign architects, whom they invited to deliver talks in Slovenia and publish their articles in the journal Arhitekt (Architect), which they launched in 1951.

Ravnikar set up his studio at the Faculty of Architecture following the model of Le Corbusier’s studio in Paris. He presented Le Corbusier’s works to his students and the general public in a special 1951 exhibition at the Moderna galerija (Museum of Modern Art). From 1946 onwards, he explored various spatial and urban‑planning problems and architectural and design issues together with his students, focused on urban growth, rural development, various forms and types of residential architecture, and traffic planning, studied the functional and technical problems of architecture, read contemporary literature, wrote a great deal himself and encouraged his students to read, engage in theoretical research and think critically. As he wrote in the journal Arhitekt, “to learn architecture primarily means to get to know the world of function, material and constructions, and the world of forms, while developing the ability and courage to solve concrete architectural tasks.”

The development plans for new residential areas (e.g., the residential area of the Mestni ljudski odbor, City People’s Council, in the Šiška neighbourhood in Ljubljana), the design proposal for Novi Beograd (New Belgrade), the morphological plan for Nova Gorica and so on were created as part of his university classes immediately after the war.

In the 1960s, Scandinavian architectural and urban‑planning experience aroused Ravnikar’s interest. At that time, Scandinavia played a leading role in urban planning, having rapidly cleaned up after the war and begun tackling complex problems of urban and regional development and housing. For example, Copenhagen received a general urban development plan as early as 1948, and Helsinki and Stockholm received theirs in 1949 and 1952. Ravnikar paid several visits to Denmark and especially Sweden, where many other Slovenian architects were working at that time. He delivered talks on Yugoslav architecture in Oslo, Copenhagen and Stockholm on several occasions, he got to know various architects, including the leading Stockholm urban planner Sven Markelius, and became acquainted with the ideas of residential neighbourhoods, new types of housing, materials and technologies.

He then developed the new ideas he brought from Scandinavia with his students as part of his classes, and also tested them in his own urban‑planning and architectural projects. A study of a development of Ljubljana along radials was created as part of his classes as early as 1955. This study summarises the ideas from his pre‑war design proposal for Ljubljana and improves them with new ideas, such as those presented in the comprehensive urban development plan for Copenhagen known as the “Five Finger Plan” and the comprehensive urban development plan for Stockholm. In these studies, Ravnikar proposed 400‑metre wide city corridors built up with a sequence of residential neighbourhoods separated by narrow green corridors. He proposed high‑rises with special accents at public transport stops, with the building profile dropping from the centre towards the edges and finally ending in low single‑family houses. He preserved non‑built‑up green spaces between the corridors extending all the way to the city centre. These studies of a star‑shaped development of the city formed the basis for the comprehensive urban development plan for Ljubljana, which was prepared by a group of Ravnikar’s younger students in 1965 at the newly established Okrajni zavod za urbanizem (Ljubljana Urban Planning Office).

Ravnikar was also intensely involved with housing research. Influenced by Swedish practices and international housing research, together with his students between 1956 and 1958 he developed a model of a residential neighbourhood as a basic organisational unit of urban planning. The sample model neighbourhood unit for 5,000 residents was designed by his students Mitja Jernejec, Majda Dobravec, Janez Lajovic and Janja Lap, and was presented at the exhibition Stanovanje za naše razmere (Housing for Our Circumstances) in Ljubljana in 1956 and at the exhibition Porodica in domačinstvo (Family and Household) in Zagreb, and published that same year in the journal Progres. The first residential neighbourhoods in Ljubljana were built in the 1960s in the Bežigrad area (BS5), and became the basic type of organised residential construction in the 1970s and 1980s. The initial urban‑planning concept of residential neighbourhoods, in which high‑rises and free‑standing long narrow apartment buildings and tower blocks surrounded by green areas predominated, kept changing. In the 1980s, more traditional urban forms were introduced, such as streets and squares, under the influence of postmodernism. In parallel, a residential typology ranging from simple long apartment buildings to tower blocks to terraced apartment buildings was developed; for single‑family homes, the concept developed from free‑standing houses via terraced houses to houses with interior courtyards, and the construction technology developed from traditional brick to prefabricated construction.

In addition to teaching and theoretical work, Ravnikar also participated in design competitions in Slovenia and abroad, and produced many designs and buildings in Slovenia and elsewhere. He participated in the design competitions for or the construction of practically all important urban areas, building the forestry institute, the student dorms in Rožna dolina, the Ljudska Pravica Newspaper Building, the faculty of civil engineering, the apartment buildings in the Prule neighbourhood, the residential high‑rises on Štefanova ulica (Štefan Street) and Pražakova ulica (Pražak Street) and on Hrvatski trg (Croatia Square), and the Ferantov vrt (Ferant Garden) housing complex were built based on his plans. He also participated in design competitions for the northern and southern parts of the city centre, the Delo Newspaper Building, the Ruski car (Russian Tsar) neighbourhood and more.

Ravnikar’s lifetime achievement in Ljubljana was undoubtedly the construction of Trg revolucije (Revolution Square), which took place over more than twenty years. He produced the first design proposal for it in 1958, when the first discussions began about erecting a central monument to the communist revolution in Ljubljana. At that time he suggested that the monument be placed in a prominent square in the form of a Greek agora that would house a state administrative office building. He envisaged the square at the location of the convent garden in front of the Slovenian parliament building. His winning 1960 design also envisaged the entire complex of the new centre as a monumental square in front of the parliament building, which would provide a backdrop for the central monument to victory and revolution. He designed two high‑rise buildings, one for the state administration and another for business offices, which would symbolise Slovenian political and economic power. Construction was interrupted in the 1960s due to financial problems, and only resumed in the 1970s based on a modified plan. In the new plan, Ravnikar lowered the two high‑rises by half. They were then purchased by Ljubljanska banka and Iskra commerce, and next to them a department store was built in the square. The entire complex thus changed from an administrative centre into a commercial business centre and the monument to the revolution was moved to the edge of the square. In the 1980s, the Kulturno‑kongresni center Ivana Cankarja (Ivan Cankar Cultural and Congress Centre) was built based on Ravnikar’s plans. This was the most important cultural building in post‑war Slovenia.

As the Belgrade‑based architect Mihajlo Mitrović wrote in his article dedicated to Edvard Ravnikar, this project by Ravnikar had an impact throughout Yugoslavia: “If one has to point a place in the country in which the greatest urban‑architectural result has been achieved in post‑war Yugoslavia, this is definitely Trg Revolucije (Revolution Square) in Ljubljana. It is a completely new part of the city, based on modern designs, and entirely executed. It features several important structures with many functions . . . The entire complex was designed by the master architect Edvard Ravnikar.”

In addition to Ravnikar, Edo Mihevc also taught a class at the School of Architecture from 1946 onwards. He gave lectures on residential and industrial buildings, and focused more on practical architectural projects. He built the Litostroj industrial complex and a residential area next to it immediately after the war, and later on he built several key buildings in the city centre; for example, the Kemija Impeks office building (1953–1955), the Kozolec residential and office building (1953–1957) and the Metalka commercial business building (1959–1963). He also worked in the Littoral (i.e., Gorizia and Trieste) throughout this time, where he developed a specific regional Mediterranean version of modernism. In 1959, he was commissioned to prepare a regional plan for the Slovenian coast from Debeli rtič (Fat Point) to Sečovlje, which covered the entire Slovenian coast and its countryside in great detail at the level of a morphological scheme.

In addition to the teachers Edvard Ravnikar and Edo Mihevc, their students also shaped the Ljubljana cityscape through their work in the second half of the twentieth century. The most important representatives of the first group of students included Savin Sever (the Učne delavnice, Study Workshops Building, 1962–1963; the Tiskarna Mladinska knjiga, Mladinska Knjiga Printing Office, 1963–1966; the Astra Building, 1963–1970; the Merkur Department Store, 1968–1970), Milan Mihelič (the Gospodarsko razstavišče, Ljubljana Exhibition and Convention Centre, 1958–1980; Konstrukta,1965–1966; Slovenijales Department Store, 1974–1980; international telecommunications centre ATC, 1972–1978; high‑rise S2 at Bavarski dvor, 1969–1980), Ilija Arnautovič, Stanko Kristl, Miloš Bonča, Danilo Furst, Majda and France Ivanšek, Janez Lajovic and Grega Košak. The most important representatives of the second group were Vojteh Ravnikar, Janez Koželj, Jurij Kobe and others. However, this already extends to the twenty‑first century.

Conclusion

Ljubljana developed at the intersection between north and south, and east and west for more than two thousand years. Every period from prehistory onwards left traces in the image of the city that shaped its present identity.

Ljubljana is connected with important historical figures whose impact extends far beyond the Slovenian borders: Primož Trubar, Johann Weikhard von Valvasor, Sigismund Zois, France Prešeren, Max Fabiani, Jože Plečnik and Edvard Ravnikar. Each of them made a contribution in his own time to raising the city’s European profile.

Over the past one hundred years, Ljubljana was part of four different countries: from the Austro‑Hungarian Empire, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and communist Yugoslavia to the independent Republic of Slovenia. It changed from an insignificant provincial centre into a modern national capital, which despite its small size can rival many larger and more important cities in Europe. The twentieth‑century city reflects a tradition that was shaped through the works of Camillo Sitte, Max Fabiani, Jože Plečnik and Edvard Ravnikar. The basic idea of a modern city was developed by Fabiani, to which Plečnik added a symbolic meaning. Ravnikar then relied on this tradition and directed the ideas of his predecessor to the most modern developments in post‑war architecture.

Ravnikar envisioned Ljubljana’s future in the following manner: “There won’t be a megacity here, we won’t have a Slovenian TV satellite and it won’t serve as a world centre of science and culture and so forth, but it will most likely be a sum of the right and wrong actions and projects . . . . There will always be a large enough gap between ideals and the urban‑planning reality that can only be reduced through serious and long‑lasting effort . . .” What Ravnikar wrote back in 1979 still applies today. Compromises between desires and the reality, and between progress and tradition, will have to continue to be sought in the future as well. And this is also the vision of future urban development.

1 Facsimile of a document from 1112–1125 that Peter Štih discovered at the Chapter Archive of Udine in Friuli, Italy; Peter Štih: Castrum Leibach, Ljubljana, 2010.

2 The town hall was built on Mestni trg (Town Square) in 1484. Its facade featured two magnificent life-sized statues of Adam and Eve. The town’s residents were very proud of them and they recommended anyone that visited the town to go see the town hall and the two statues.

3 Published by W. M. Endter, Nüremberg, 1688.

4 France Prešeren nicely described how Ljubljana residents awaited the construction of the railway in his poem “Železna cesta” (The Iron Road): “The iron road is drawing nigh, / My darling looks forward to this day, / From Ljubljana to other towns she’ll fly, / Like a little bird on its way.”

5 Slovene edition: Camilo Sitte: Umetnost graditve mest (Slovenian translation of the Der Städtebau . . .), Ljubljana, 1997.

6 Max Fabiani: Poročilo o splošnem regulacijskem načrtu za Bielsko, in: Max Fabiani, O kulturi mest, ed. Marco Pozzetto, Trieste, 1988, p. 63.

7 Max Fabiani: Vicenza, in: Max Fabiani, O kulturi mest, ed. Marco Pozzetto, Trieste, 1988, p. 23.

8 Max Fabiani: Poročilo k načrtu občne regulacije deželnega stolnega mesta Ljubljane, 2nd edition, Vienna, 1899.

9 At the invitation of the municipal council, a draft urban development plan was also submitted by one of the best-known Vienna urban planners, Camilo Sitte (1843–1903), as well as by Max Fabiani (1865–1962), a native Slovenian architect and urban planner, and one of the most prominent Slovenian experts in Vienna at that time. Fabiani’s plan formed the basis for the city’s post-earthquake reconstruction.

10 Stavbinski red za občinsko ozemlje deželnega stolnega mesta Ljubljane (Building Regulations for the Municipal Territory of the Capital of Ljubljana), Deželni zakonik za Vojvodino Kranjsko, 21, 1896.

11 Jože Plečnik: Študija regulacije Ljubljane in okolice, Dom in svet, 1928, appendix 4. Jože Plečnik: Študija regulacije severnega dela Ljubljane, Dom in svet, 1929, p. 91.

12 Max Fabiani: O umetnosti Jožeta Plečnika, in : Max Fabiani, O kulturi mest: Spisi 1895–1960, ed. Marco Pozzetto, Trieste, 1988, p. 178.

13 “Arhitektura”, L'architecture d'Aujourd'hui, 1932, no. 6, p. 101.

14 The Le Corbusier Foundationin Paris keeps data on twelve Yugoslav architects, among them seven Plečnik’s students. Bogo Zupančič: Plečnikovi diplomanti v Le Corbusierovem ateljeju, Ljubljana, pp. 99–118.

15 Edo Ravnikar: Kratek oris modernega urbanizma v Sloveniji, paper presented at the First Conference of Yugoslav Architects in Dubrovnik in 1950, conference proceedings, Ljubljana, 1950, p. 8.

16 Vzgoja arhitektov: Študijske prakse na fakultetah za arhitekturo, Arhitekt I, 1951, no. 1, p. 48.

17 Martina Malešič: Pomen skandinavskih vplivov za slovensko stanovanjsko kulturo (The Significance of Scandinavian influences for Slovenian Housing Culture), Doctoral Thesis, Faculty of Arts, Department for Art History, University of Ljubljana, 2013.

18 Journal Progress, Zagreb, 1958, the issue dedicated to the exhibition Porodica i domačinstvo.

19 Mihajlo Mitrović: Edvard Ravnikar – spomini, in: Hommage à Edvard Ravnikar 1907–1993, ed. France Ivanšek, Ljubljana, 1995, p. 270.

20 Ljubljana čez 50 let, Tedenska tribuna TT, Ljubljana, 1954 (4 Nov.), no. 44, p. 7.

21 Edvard Ravnikar: Ljubljana 2000, AB, 1979, nos. 44–45, p. 7.